Welcome back, beautiful mind! Let’s talk about something that sounds like it belongs in a neuroscience textbook but hits uncomfortably close to home if you’ve ever stared into the void instead of finishing that email: Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome (CDS).

CDS used to go by the less catchy name “Sluggish Cognitive Tempo,” and honestly? That label did no favors. It conjured up the image of a sleepy sloth rather than a complex neurocognitive pattern tied to attention dysregulation, internalization, and ADHD subtype expression.

But here’s the thing: CDS isn’t just about being “lazy” or “unmotivated.” It’s about what’s happening under the hood—and neuroscience has a lot to say about it.

🧩 What Is Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome (CDS)?

CDS is a set of symptoms that can co-occur with ADHD—especially the inattentive type—but is neurologically distinct in some key ways. People with CDS tend to experience:

Excessive daydreaming

Mental fog or “spacing out”

Low mental energy or processing speed

Lethargy, drowsiness, or hypoactivity

Staring into space (not zoning in or zoning out—just zoned elsewhere)

Slow responses and trouble sustaining alertness

The core difference? While traditional ADHD is often marked by impulsivity and hyperactivity, CDS leans more into the realm of internal distraction, almost like the brain is buffering… constantly.

⚡️Quick Analogy:

If ADHD is like having 30 open tabs and music blaring, CDS is like staring at a frozen screen with the spinning rainbow wheel of doom. You're not doing “nothing”—your brain’s just caught in an infinite loading loop.

“The Two ADHD Paths”

🧬 The Neuroscience Behind CDS

Let’s nerd out for a second, shall we? 🤓

At the heart of CDS is cortical underarousal—meaning your brain isn’t getting enough activation to sustain engagement or task initiation. This often comes from disruptions in:

1. Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Systems

The brain’s “go juice,” dopamine and norepinephrine, are often low in people with ADHD. In CDS, these levels may be even more deficient, especially in areas like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (task focus), default mode network (mind-wandering), and reticular activating system (arousal and alertness).

2. Default Mode Network (DMN) Overactivity

The DMN is your brain’s “idle mode.” It activates during rest, mind-wandering, and self-reflection. In CDS, the DMN tends to intrude on active tasks—causing dissociation, daydreaming, and the dreaded mental drift even when you want to focus.

3. Hypoarousal

Neuroscientific imaging has shown reduced blood flow and activity in the frontal lobes of individuals with CDS. This hypoarousal feels like cognitive gravity pulling you down, even when motivation is high.

🧠 So Why Do We Struggle So Much?

Let’s call it the perfect storm: low energy + low dopamine + poor executive regulation = one very disengaged brain.

This can lead to:

Procrastination from pure overwhelm (“I want to do it, but I literally can’t start.”)

Getting lost in thought loops (Think: overthinking a text reply for 20 minutes, then not sending it at all.)

Struggling with transitions and task-switching (CDS brains often freeze in place between actions.)

Difficulty with goal-directed behavior without a clear external push or emotional hook

And, worst of all, it tends to be misinterpreted by the outside world as laziness, apathy, or depression. Not fair, right?

“The CDS Iceberg”

📚 Real-Life Examples

Example 1: The Email Paralysis

You open your laptop, stare at your inbox, click a few messages, but your brain feels like it’s stuck in molasses. You read the same sentence three times and forget what it said. You end up scrolling TikTok and hating yourself for it.

Example 2: The Task Fog

You know you need to take out the trash, call your insurance, and prep for tomorrow. Instead, you’re lying on the couch in a weird existential trance, wondering if pigeons have thoughts. Two hours later: panic, guilt, shutdown.

Example 3: The Invisible Wall

You’ve had 8 hours to do the thing. You even wanted to do the thing. But the moment you sat down to start it, it was like trying to swim through cement. You physically couldn’t engage, even though the intention was there.

🧭 What Can We Do About It?

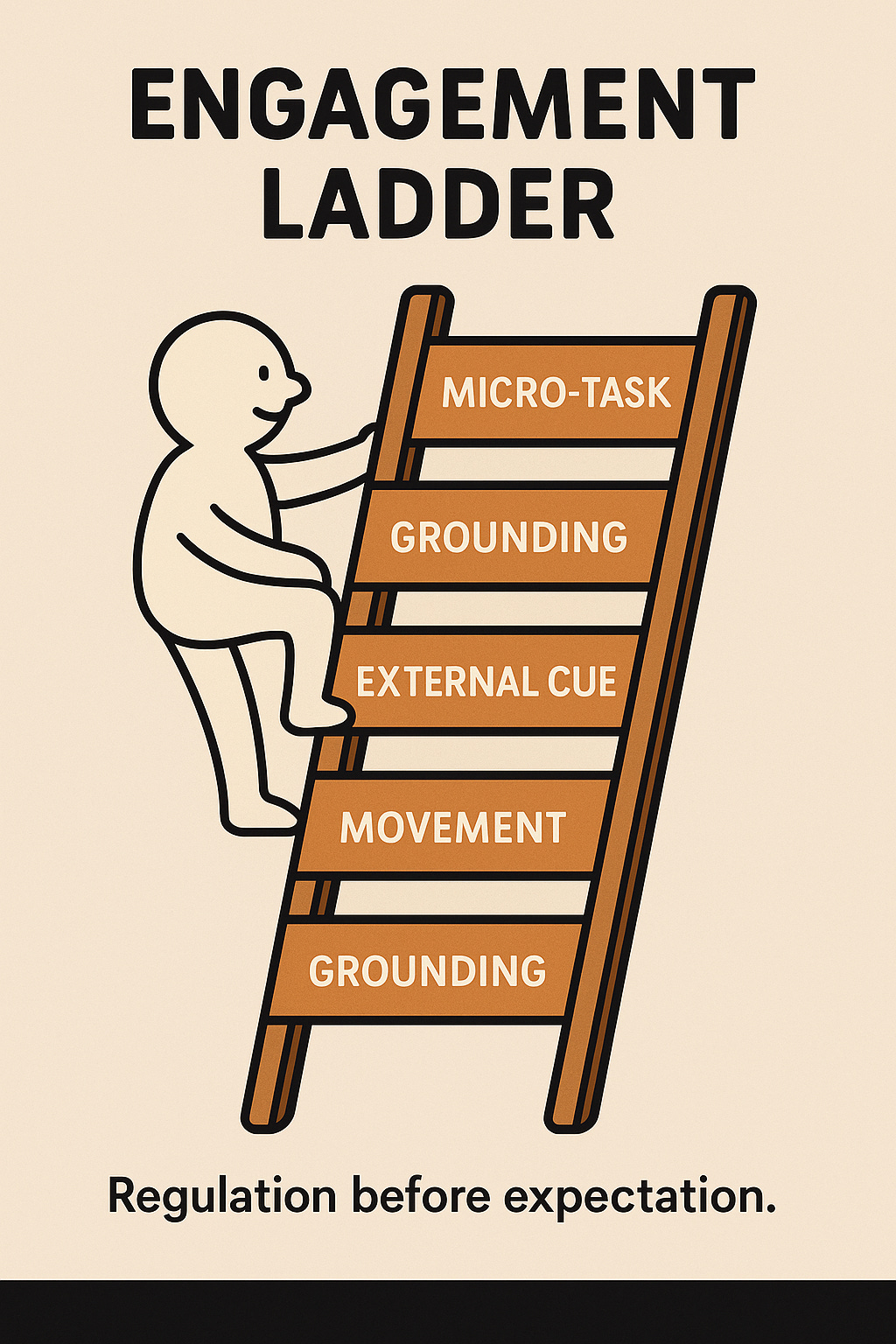

The goal isn’t to become a productivity machine—it’s to regulate your arousal system, engage your attention gently, and create enough external structure to overcome internal fog. Here’s how:

🧩 1. Activate Before You Initiate

Use body-based activation: stretch, do jumping jacks, blast a song and dance for 90 seconds.

CDS brains often need physical engagement to “wake up” before cognitive tasks begin.

🪜 2. Interrupt the Default Mode Network

Try a 5-4-3-2-1 grounding exercise before starting something hard

Use visual timers or color-coded task strips to anchor attention externally

🧱 3. Externalize Everything

Break tasks into micro-steps. “Write report” becomes: open doc → type date → write header.

Use Post-its, planners, or apps that physically pull you back into the now (like TickTick, Time Timer, or Notion)

🧠 4. Boost Arousal Mindfully

Caffeine in small amounts can help—but pair it with hydration and deep breathing.

Try cold water splashes, chewing gum, or peppermint oil—all sensory-based arousal boosters.

👯 5. Use “Body Doubling”

Work with someone nearby—even virtually. The presence of another person helps tether attention to the task, reducing the DMN takeover.

🧸 6. Compassion Over Shame

Recognize: You’re not broken. CDS is real, and it’s neurologically rooted.

Be gentle with the part of you that feels stuck. Self-judgment only deepens disengagement.

🧠 Final Thoughts: CDS Isn’t You Being Lazy—It’s Your Brain Asking for Support

Let’s rewrite the narrative.

If your brain goes into airplane mode mid-thought, it’s not a character flaw—it’s a signal. One that says, “I need something to bring me online.” You don’t have to “push through” CDS. You need to work with your brain, not against it.

Understanding cognitive disengagement syndrome gives us a lens of compassion, science, and realistic support—not shame. And when we give ourselves those tools? We shift from survival mode to something that actually works for how our brains are wired.

P.S. Share this with someone who needs to know that staring into space is not a moral failing. It’s just the brain saying, “Hold on—I’m buffering.”