AuDHD and Alexithymia: Navigating Emotions When Feelings Have No Names

Imagine sitting with a storm of emotions inside you but no clear words to describe them. A friend asks, “How do you feel?” and your mind goes blank, grasping at straws. For many neurodivergent adults, especially those with AuDHD – the overlap of autism and ADHD – this scenario is all too familiar. Often, it’s not that they don’t have feelings, but that they struggle to identify and label those feelings. This is the world of alexithymia, a separate “co-traveler” that frequently accompanies neurodivergent conditions. In this post, we’ll explore how alexithymia can co-occur with autism and ADHD, why it can create “autism-like” emotional confusion, and why recognizing it matters. We’ll also look at what this experience is like for neurodivergent adults and end with practical tips, strategies, and reflection journal prompts to better navigate the unnamed emotions.

What Are AuDHD and Alexithymia?

AuDHD is a term coined by the neurodivergent community to describe individuals who are both autistic and have ADHD. While not a formal diagnosis, AuDHD captures the unique experience of living with traits of both autism spectrum and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder simultaneously. Autistic and ADHD traits can intertwine in complex ways – for example, one person might have the autistic love of routine and the ADHD tendency to be easily distracted, making for an interesting mix of needs and behaviors. Many people identify as AuDHD to acknowledge that they navigate both these neurotypes at once.

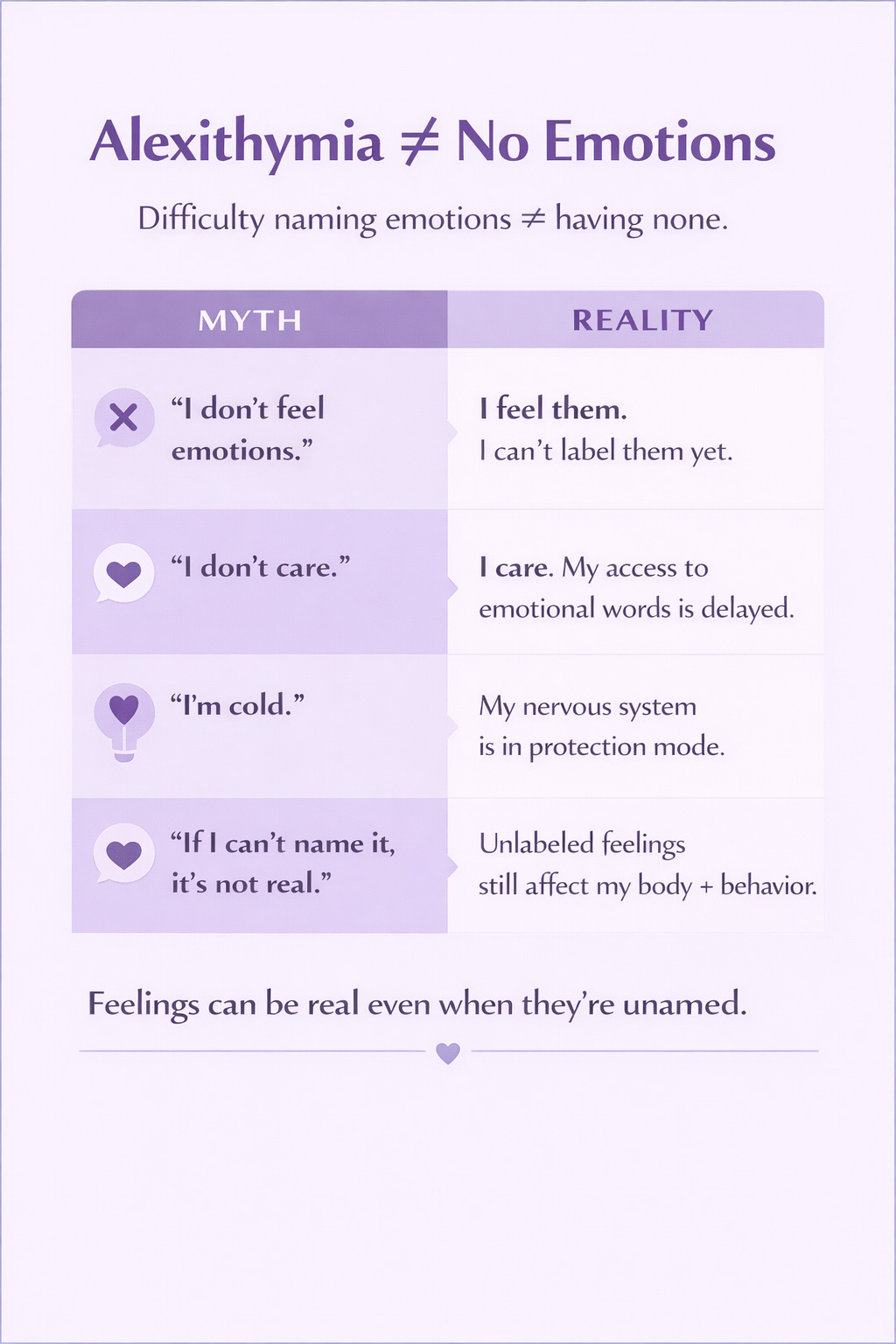

Alexithymia, on the other hand, is a term that describes difficulty in recognizing and describing one’s emotions. The word literally comes from Greek meaning “no words for emotion.” Alexithymia is not a clinical disorder in itself, but rather a trait or phenomenon. A person with alexithymia might struggle to answer questions like, “What are you feeling right now?” They often genuinely don’t know the answer, even if their body is having a strong emotional reaction. For example, they might notice a racing heart or an upset stomach – physical signs of emotions – but not connect those sensations to a specific feeling like anxiety or excitement. In essence, there’s a disconnect between the emotional experience and the ability to name or understand that experience.

It’s important to note that alexithymia exists on a spectrum. Some people have mild difficulty with identifying feelings, while others might feel almost completely “blind” to their emotional inner world. Alexithymia can occur in anyone, but it’s much more common among neurodivergent people such as those with autism or ADHD. In fact, research suggests that a significant portion of autistic and ADHD individuals experience alexithymia alongside their primary diagnosis. Many estimates indicate that roughly half of autistic people – and perhaps around 40% of people with ADHD – have notable alexithymic traits. That means if you are AuDHD, the odds of also dealing with alexithymia are fairly high.

Alexithymia: A Separate Co-Traveler on the Neurodivergent Journey

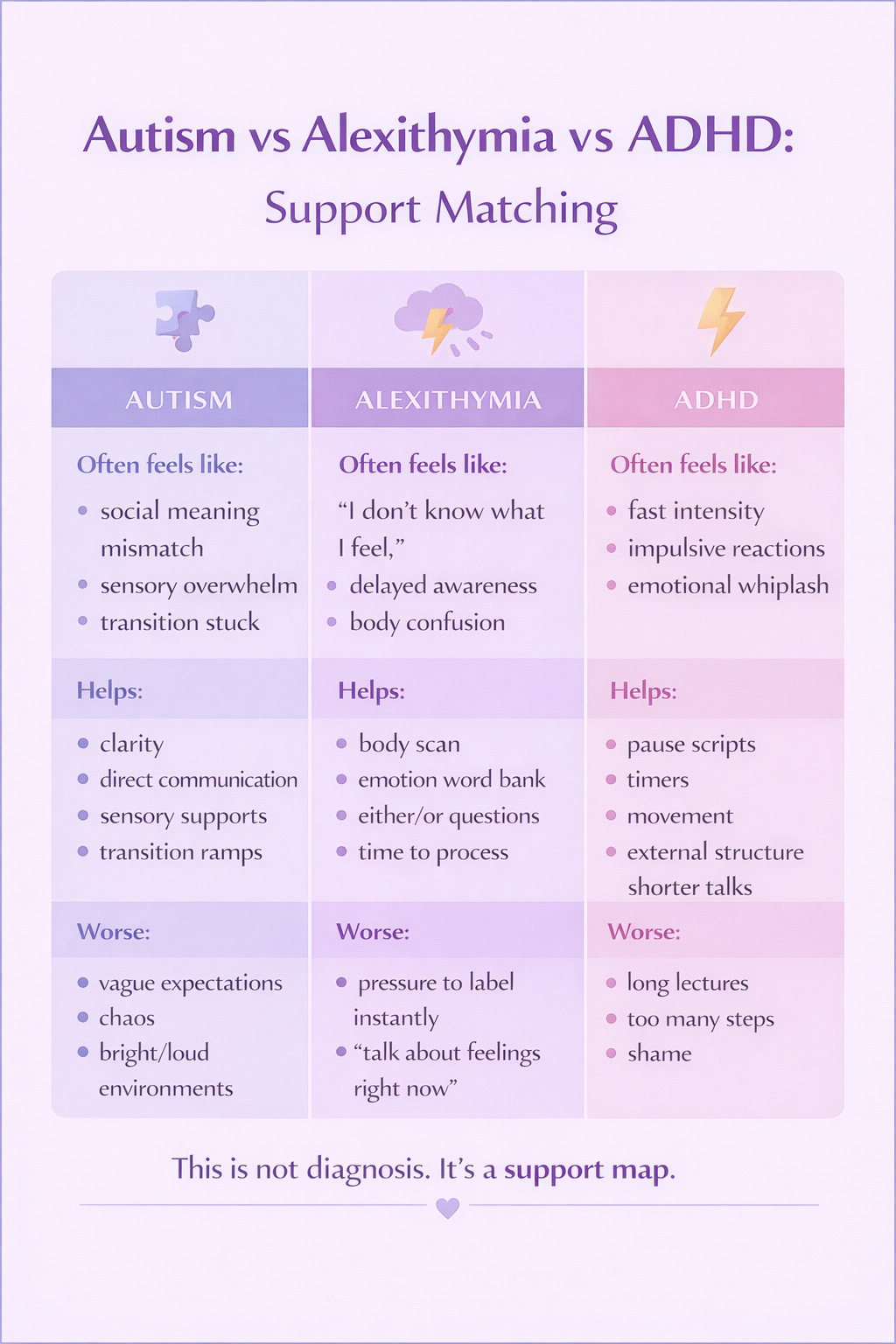

Alexithymia is best thought of as a co-traveler rather than a core feature of autism or ADHD. It often rides alongside these neurodevelopmental differences, but it is distinct. You can be autistic without alexithymia, or have ADHD without alexithymia – and conversely, a person can have alexithymia without being autistic or ADHD. However, when they do occur together, they can profoundly shape a person’s emotional life.

One reason alexithymia often gets tangled up with autism is that on the surface, some of its effects look “autism-like.” For example, a classic stereotype about autism is that autistic people lack empathy or don’t understand emotions. In reality, many autistic individuals do empathize and feel deeply. But researchers have found that when an autistic person also has alexithymia, they may indeed show limited emotional expression or struggle to read others’ feelings – not because of autism itself, but because of the alexithymia. In fact, scientists have proposed an “alexithymia hypothesis,” suggesting that a lot of the emotional confusion or apparent lack of empathy attributed to autism is better explained by co-occurring alexithymia. In other words, autism isn’t necessarily what causes someone to seem emotionally distant or unaware – it could be that this separate trait of alexithymia is at play.

This distinction is important. It means that supports differ for different needs. If a person’s challenge is coming from autism (say, sensory overwhelm or need for routine), the strategies to help them will be different than if the challenge is coming from alexithymia (difficulty identifying feelings). Recognizing alexithymia as its own “traveling companion” allows both individuals and support professionals to tailor their approach. For example, an autistic adult who has no trouble identifying their emotions might benefit more from social communication support or sensory accommodations. But an autistic adult with alexithymia might need additional help specifically with emotional awareness, like learning to interpret body signals or expand their emotional vocabulary.

Similarly, in ADHD, people often talk about emotional dysregulation – feelings that are very intense and hard to manage. But when ADHD and alexithymia co-occur, it adds another layer: the emotions might be intense and hard to pinpoint. An ADHDer might go from zero to sixty on the emotional speedometer (due to ADHD impulsivity), yet not actually realize what the emotion was until later (due to alexithymia). For instance, frustration might rapidly flare into an outburst, and only afterwards the person pieces together, “Oh, I guess I was feeling overwhelmed and anxious about that task; I didn’t recognize it at the time.” This combination can be perplexing – like a storm without a radar. You feel the impact of the emotions (thunder, lightning) but you can’t see the storm coming or map it clearly, which is confusing and sometimes scary.

Because alexithymia often co-travels with neurodivergence, many neurodivergent adults have spent years feeling like there was an extra “something” about them that wasn’t fully explained by autism or ADHD alone. If you’ve ever thought, “I know I’m neurodivergent, but why are emotions such a blind spot for me?”, alexithymia might be that missing puzzle piece. The good news is that by identifying this companion, you can start addressing it directly.

When Feelings Are Fuzzy: How Alexithymia Feels in Daily Life

So, what does alexithymia actually look like or feel like in everyday life for an AuDHD adult? While everyone’s experience is a bit different, there are some common themes that many people with alexithymia report:

Signs of alexithymia often revolve around difficulties with emotions. For example, a person might frequently say “I don’t know” when asked how they feel, or give very general answers like “I’m fine” even when they are visibly not fine. They might have delayed emotional reactions – only realizing hours later that they were angry or sad about something that happened. Emotional responses can appear flat or muted; others may perceive them as emotionally distant or unusually calm. On the inside, the individual might feel a confusing swirl or, alternatively, a frustrating emptiness where an emotion should be.

Difficulty identifying feelings in the moment: Someone with alexithymia might register that something is off – for instance, they feel agitated or notice their heart pounding – but they can’t name what the emotion is. It’s like having an internal dashboard with warning lights blinking, but no labels on the lights. You sense that you’re “not okay,” but is it anger? Anxiety? Sadness? You’re unsure. Many people in this situation default to “I’m not sure what I feel” or even “I feel nothing,” because the specific emotion is unclear. One autistic adult described it like this: “The worse I feel, the more I default to saying ‘I’m fine.’” They might only realize later that “fine” actually covered up frustration or hurt that they couldn’t articulate at the time.

Externally oriented thinking: People with alexithymia often focus on external facts and thoughts rather than their inner feelings. In conversations, an alexithymic AuDHD person might be very logical or factual when others are sharing feelings. It’s not that they’re cold; they’re just more comfortable discussing what happened or what they think about it instead of how it made them feel (because they genuinely have trouble grasping how it did). For example, if asked about a distressing event, they might recount the details of what occurred and what actions they took, but pause blankly when probed about their emotional reaction.

Misinterpreting physical cues: Because alexithymia blurs the line between emotional signals and physical sensations, neurodivergent folks might confuse emotions with other states. You might feel tired or have a headache and not realize those physical signs are because you’re stressed or upset. Or you might assume “I’m just hungry” when in fact you’re feeling anxious. Without a clear translation of bodily signals, one can mix up an emotional state with something like fatigue or hunger. This can lead to needs going unmet – for example, you might try to fix the “hunger” with a snack, but what you really needed was to address anxiety or sadness.

Emotional aftershocks instead of immediate reactions: It’s common for those with alexithymia to have a delayed understanding of their feelings. You might only figure out what you were feeling once you’ve had time to mentally replay the situation. Journaling or analyzing an event after the fact often brings clarity that wasn’t there in the heat of the moment. A neurodivergent adult might leave a stressful work meeting thinking they were fine, and that evening suddenly feel a rush of anger or tears when processing it. In hindsight they realize, “Actually, I was really embarrassed and annoyed in that meeting, I just didn’t identify it at the time.” This delay can be bewildering – both to the person and to those around them. Loved ones might wonder, “Why are you upset about it now?” not realizing the individual was unable to pinpoint the upset earlier.

**“Autopilot” or simulating emotions: Some AuDHD individuals describe coping by intellectually figuring out what emotion is expected in a situation and almost performing it, because they can’t feel it clearly. For instance, if something sad happens (say, a colleague’s pet passed away), they know from context that sadness or empathy is the appropriate emotion. They care and want to respond kindly, so they might mimic the outward expression – offering condolences, making a sympathetic face – even if internally they can’t actually feel the sadness in a tangible way. It’s not about being fake; it’s often about doing what seems right when your own emotional compass isn’t giving you strong readings. This kind of “acting” is a survival skill, a form of masking that autistic and ADHD people might be all too familiar with. However, it can be draining and leave one feeling like they’re always one step removed from the genuine emotional experience.

Impact on relationships: Alexithymia can make interpersonal interactions tricky. Friends or partners might get frustrated with the alexithymic person’s hesitance or inability to share feelings. You might hear things like, “You never tell me what’s going on inside,” or “Do you even care? You seem so detached.” On the flip side, the alexithymic individual often does care deeply but feels helpless because they truly don’t know what’s going on inside themselves to be able to share it. This mismatch can lead to misunderstandings — for example, a partner might interpret “I don’t know how I feel” as dodging the question or withholding, when really it’s an honest statement. Without clear communication, both sides can feel hurt: the loved one might feel shut out, and the alexithymic person might feel pressured or guilty for not meeting emotional expectations. It’s like speaking different languages – one speaks “emotionalese,” the other speaks “factualese,” and they struggle to translate.

Internal confusion and frustration: Being alexithymic isn’t just frustrating for others; it’s often deeply frustrating for the person themselves. Many neurodivergent adults with alexithymia have an internal dialogue of “What is wrong with me? Why can’t I just feel what others feel or know what I’m feeling?” It can affect self-esteem and mental health. Some describe feeling “broken” or alien because emotions – which seem to come so naturally to others – feel like a mystery to them. This can sometimes contribute to anxiety or depression. In fact, not understanding or processing your own emotions can lead to bottled-up stress, which may manifest as general anxiety or a sense of numbness that overlaps with depression. It’s not uncommon for alexithymic individuals to only realize they’ve been deeply stressed or unhappy after it reaches a tipping point (like a burnout or a meltdown), because they missed the earlier emotional cues that something was wrong.

Emotional meltdowns or outbursts: Ironically, alexithymia doesn’t prevent emotions from happening – it just makes it hard to recognize and deal with them in real-time. What can happen is that emotions build in the background, under the radar, until they overflow. Think of it like a pot on the stove that’s boiling with the lid on: if you’re not monitoring it, eventually it boils over. A neurodivergent person might experience a sudden crying spell, panic attack, or rage outburst “out of the blue,” surprising everyone including themselves. On reflection, it turns out there were stressors and feelings brewing, but because they weren’t identified and managed along the way, they reached a bursting point. This cycle – not feeling anything specific until it’s too much – can be exhausting and even frightening. It also reinforces the importance of learning strategies to catch emotions earlier, if possible.

Despite these challenges, it’s crucial to emphasize that having alexithymia does not mean someone lacks emotions or empathy. They often have profound care for others and do feel emotions; the core issue is access. The feelings might be there, but behind a thick fog or locked behind a door that only opens with the right key. Understanding this can create more compassion both for oneself and from others. It shifts the perspective from “This person doesn’t care or is just being difficult” to “This person is having trouble tuning into something that’s actually there.” And that shift in understanding is the first step toward better support and coping.

Why Recognizing Alexithymia Matters for Neurodivergent Adults

Identifying alexithymia as a separate piece of the puzzle is empowering. It allows neurodivergent adults (and those supporting them) to target specific strategies for this issue, rather than feeling stuck or misinterpreting the problem.

For example, consider an autistic adult who consistently says “I’m fine” or “I don’t know” when upset, and feels overwhelmed out of nowhere. If everyone assumes “That’s just autism”, they might focus on autism-related supports like social skills training or sensory breaks. Those can be very helpful for other reasons, but they won’t directly teach emotional awareness. By recognizing alexithymia, one could instead introduce tools like emotion identification exercises or therapy specifically aimed at connecting mind and body signals. It’s like adjusting the lens to the right problem.

Recognizing alexithymia also helps break harmful stereotypes. As mentioned, many of the old clichés about autistic or ADHD folks being “uncaring” or “emotionless” are flat-out wrong. When we understand how alexithymia works, we see that a lack of visible emotion doesn’t equal lack of feeling or empathy. This recognition fosters better communication: a neurodivergent person can say to a loved one, “I sometimes really can’t tell what I’m feeling in the moment – but give me some time or another way to process, and I will get back to you,” rather than the loved one assuming disinterest. It also means clinicians and supporters can adapt therapies – for instance, standard talk therapy might need to be adapted if a client can’t easily identify feelings; they might work on building that skill first, or use creative methods like art or biofeedback.

In short, knowing that alexithymia is in the mix validates the experiences of neurodivergent adults who have always felt a bit lost in the realm of emotions. It says: You’re not broken or alone – there’s a name for this experience, and there are ways to work with it. With that in mind, let’s look at some of those ways.

Strategies for Navigating Alexithymia

Living with alexithymia (especially as an autistic or ADHD adult) can be challenging, but there are strategies and tools that can help improve emotional insight and communication. Here are some approaches to consider:

Build Your Emotional Vocabulary: Expand the list of emotion words you know and use. Sometimes we genuinely don’t have the words, which makes it harder to label subtle feelings. Using resources like an emotion wheel or lists of feeling words can spark recognition. Start with the basics (happy, sad, angry, scared, etc.) and then learn nuanced words (e.g. “frustrated” vs. “angry,” “anxious” vs. “scared,” “content” vs. “happy”). Keep a cheat sheet if you like. When you journal or think about your day, refer to the list: “Did I feel any of these today?” Even if you’re not sure, circling a couple of candidate emotions is progress. Over time, you’ll likely get more comfortable differentiating feelings when you have names for them.

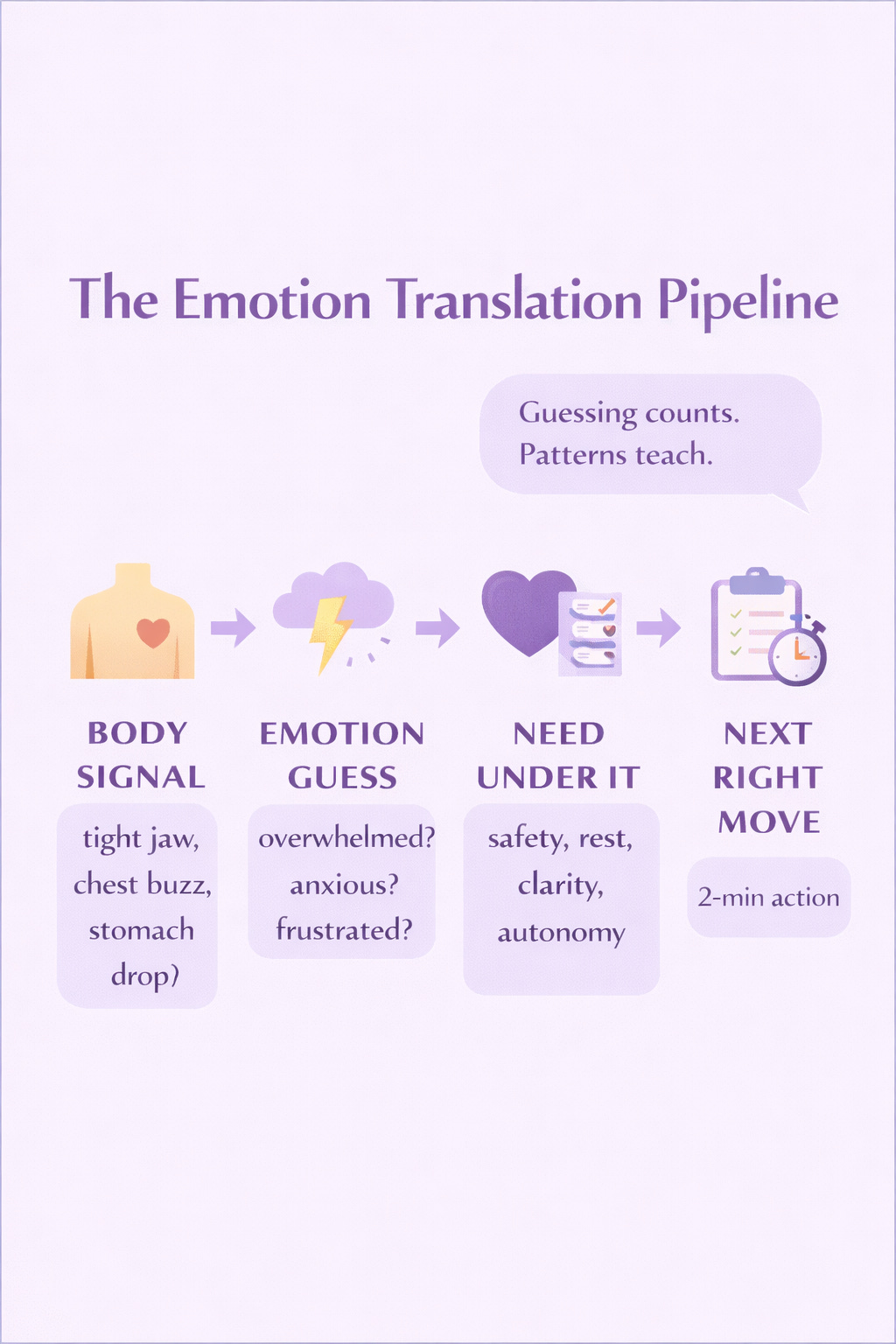

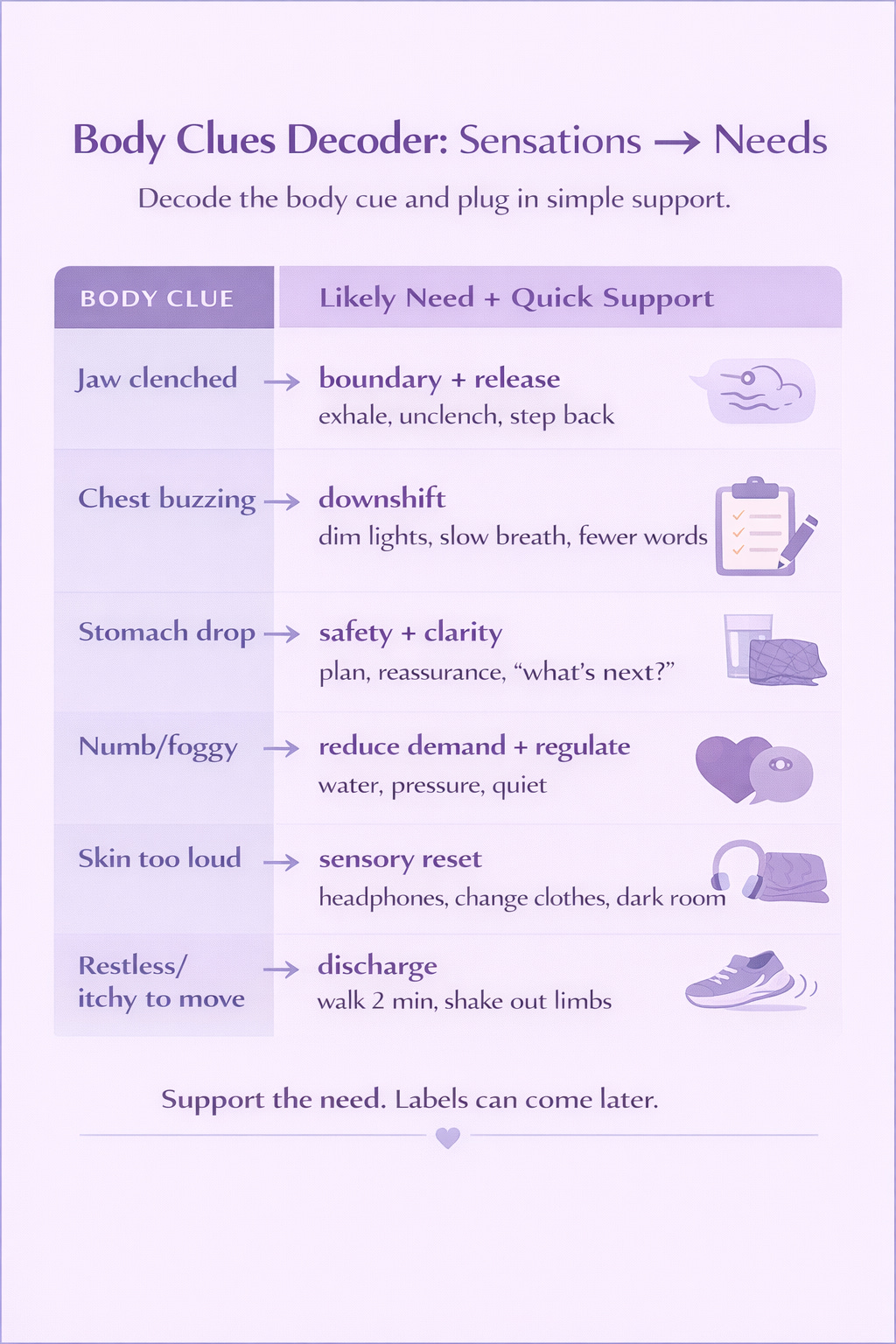

Practice Interoceptive Awareness: Interoception is the sense of your internal body signals – things like heartbeat, stomach sensations, muscle tension, temperature, etc. Since our internal signals are the clues our brain uses to identify emotions, improving interoceptive awareness can help with alexithymia. Try short exercises to tune into your body. For example, a couple of times a day, pause and do a “body scan” – check in from head to toe: Is my jaw clenched or relaxed? How is my breathing? Is my heart beating fast or slow? Do I feel any tightness or butterflies anywhere? Don’t worry about naming an emotion yet; just note the sensations. Another practice is to intentionally evoke sensations in a playful way: hold a cold ice cube and notice how your body reacts, or do 10 jumping jacks and feel your heart pumping. Then see if you can attach a description to those sensations (cold, startled, warm, energized, etc.). These practices build the habit of connecting physical feelings to descriptive words, which is the same foundation used to later identify emotions (since emotions usually come with physical sensations too).

Use Journaling or Voice Notes: When it’s hard to speak your feelings in the moment, it might help to express them in a more private, extended way. Journaling is a great tool for this. After a significant event or at the end of the day, try writing about what happened and how you think you might have felt. Don’t worry if you’re unsure – you can even write “I’m not sure what I felt, maybe I was upset because my stomach was in knots.” The act of writing can often bring clarity; some people find that as they write, they discover “aha, I was really disappointed and worried, that’s why I felt sick.” If writing by hand or typing is not your thing (especially for ADHD folks who might find it tedious), consider voice-recording your thoughts in a private audio journal. Talk out loud about the day and listen for clues in your own voice – do you sound angry, sad, excited when recounting something? Often our tone or the metaphors we use (“it was like a slap in the face”) can reveal feelings we didn’t label at first.

Create an “Emotion-Body” Map: This is a personal project that can be insightful. Take a simple outline of a human body (you can draw one or print a blank silhouette) and think about common emotions, then mark where you feel them in your body. For example, you might recall, “When I’m anxious, I often get a tight chest and sweaty palms,” so mark chest and hands for anxiety. “When I’m angry, my face feels hot and my shoulders tense,” mark those for anger. This might require some introspection or recall, but it can serve as a reference guide. Next time you feel a weird sensation – say, your shoulders are tight and your face is warm – you can look at your map and think, “These sensations match anger on my map. Could I be angry right now about something?” It’s not always one-to-one, but over time this body-emotion map becomes a personalized decoder for your feelings.

Slow Down Reactions: For ADHD brains especially, emotions can trigger quick actions. Try to build in a pause when you start feeling anything rising (even if you don’t know what it is). This could mean counting to ten, taking a few deep breaths, or physically stepping away for a moment. The goal is to give your thinking brain a chance to catch up with your emotional brain. During that pause, do a quick body check or inner check: What might have caused this sudden feeling? Did someone’s comment offend me? Am I feeling overwhelmed by too much noise? Even if you can’t identify it fully, the pause can sometimes prevent an impulsive reaction that you might regret. It’s perfectly fine to tell people, “I need a moment to gather my thoughts” or “Give me a second, I’m not sure how I feel yet.” Buying yourself time can reduce the pressure to respond with a feeling you haven’t identified.

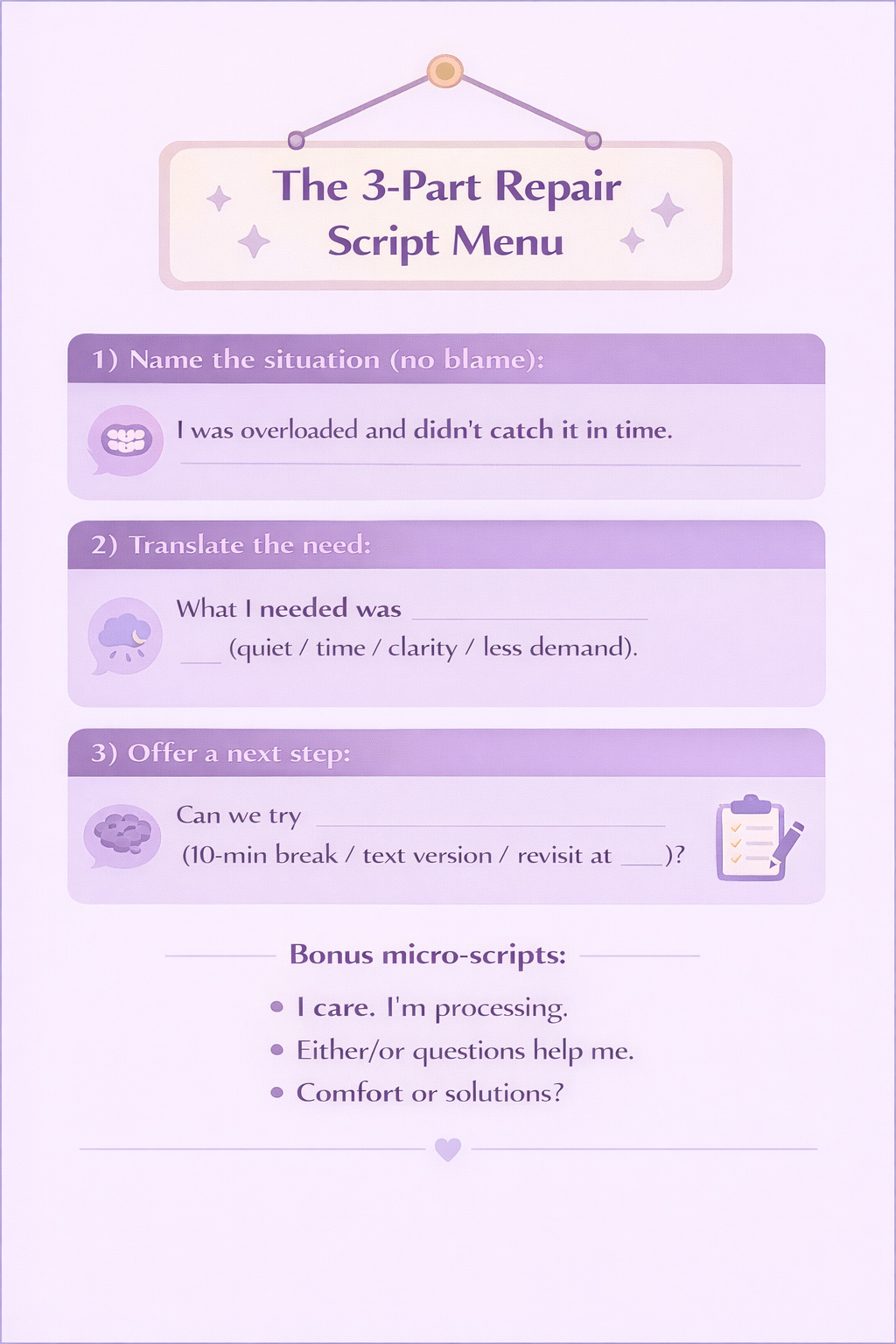

Communicate Your Needs to Others: It can be very helpful to let close friends, family, or partners know about your alexithymia. Educate them that “I often truly don’t know what I’m feeling in the moment, but I do care and I do feel – it just might take me time to figure it out.” By setting this expectation, you take away some of the tension in emotional conversations. Loved ones then understand that if you say “I don’t know,” you’re not being dismissive. You might also suggest alternative ways to connect: for instance, writing an email or text about feelings if face-to-face talks are too hard, or using scales (“I’m about 4 out of 10 upset”) if that’s easier than naming an emotion. Additionally, encourage them to gently help if appropriate: they might ask, “Do you think you’re feeling more angry or more sad about this? Or maybe something else?” Sometimes an outside prompt can help you reflect. The key is that the people around you become allies in decoding emotions rather than judges.

Consider Professional Support (with someone who gets it): Therapy and counseling can be beneficial, but it’s important to find a professional who understands neurodivergence and alexithymia. Traditional therapy that constantly asks “How did that make you feel?” can be frustrating if you don’t know! Look for therapists who are neurodiversity-affirming or who explicitly mention working with autism/ADHD or emotion-processing issues. Therapies that might help include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with a focus on identifying thoughts and body sensations as bridges to emotion, or mindfulness-based therapies that train you to notice present-moment feelings non-judgmentally. Some people also benefit from more experiential therapies like art therapy or somatic (body-focused) therapy to bypass the verbal labeling hurdle and express feelings in other ways first. Group therapy or support groups with other neurodivergent adults can also normalize the experience; hearing others articulate similar struggles can reduce your self-blame and give you new ideas to try. Remember, the goal of therapy in this context isn’t to magically give you the emotional awareness of a neurotypical person, but to help you find your own strategies for better recognizing and coping with what you feel.

Be Patient and Kind to Yourself: This is more of a mindset than a strategy, but perhaps the most important. It’s easy to get frustrated at yourself when you consistently can’t identify your feelings or when you only realize later what you felt. You might be tempted to call yourself “bad at feelings” or compare yourself to others who seem to navigate emotions with ease. Try to cultivate some self-compassion around this. There is no “wrong” way to feel. Every person’s emotional landscape is different, and needing extra time or tools to understand yours is perfectly okay. Remind yourself that emotions are complicated for everyone to some degree, and you are actively working on it – that effort is admirable. When you do make a breakthrough (like identifying an emotion in the moment, or successfully communicating to a friend that you’re upset about something), celebrate it. It’s a big deal! Over time, those small victories will add up, and your confidence in handling emotions will grow.

Reflection Journal Prompts for Exploring Your Emotions

Sometimes, structured reflection can help you delve into your feelings in a safe, private way. Here are a few gentle journal prompts designed for neurodivergent adults dealing with alexithymia. You can write about them, talk out loud to yourself, or even just think them through in a quiet moment. There are no right or wrong answers – the purpose is to spark insight and self-understanding.

Prompt 1: Think of a recent situation that was emotionally confusing. Describe what happened and what you noticed in your body at the time (e.g., “My heart was racing and I had a lump in my throat”). Even if you’re not sure what you felt, list any possible emotions that could fit that physical state or situation (for example, maybe it was anger, anxiety, excitement – or some mix). How did you eventually realize what you were feeling, or is it still a mystery?

Prompt 2: Describe your emotions using a metaphor or comparison. Sometimes indirect language can express feelings that we can’t label plainly. For instance, “My emotions lately feel like a sealed jar – I can shake it and sense something’s inside, but I haven’t opened it yet,” or “I feel like a computer with too many tabs open, but I can’t see what all the tabs are.” Come up with your own analogy for your current emotional state or your experience of alexithymia. What does this reveal to you about what you might be feeling?

Prompt 3: Recall a time you had an emotional reaction that surprised you. Maybe you burst into tears watching a movie and didn’t know why, or you snapped at someone and later realized you were more stressed than you thought. Write about that incident. What do you think might have been happening under the surface? Were there any early signs you overlooked at the time? In hindsight, what emotion do you think was building up?

Prompt 4: List a few basic emotions (such as joy, anger, fear, love, stress, etc.) and for each one, write down how you know when you’re feeling it – or if you’re not sure, write down how you think you might recognize it. For example, “I know I’m happy when I catch myself humming or when my body feels light,” or “I’m not entirely sure what love feels like for me, but I notice I want to be around the person and do things for them.” This exercise can be tough, but it’s okay to speculate. It helps you begin to define markers of each emotion for yourself.

Prompt 5: Journal about any progress or changes* you’ve noticed in your emotional awareness. Over the past weeks or months, have you had moments of clarity where you did identify an emotion in real-time or felt something you could name? What helped that happen – was it a quieter environment, a prompt from someone, using one of the strategies above? Conversely, are there patterns to when it’s hardest to know your feelings (for example, when you’re under a lot of pressure, or when the feelings are subtle versus very intense)? Recognizing these patterns is a win in itself, so reflect on them.

Remember, the journey with alexithymia is not about turning into an emotional guru overnight. It’s about baby steps: gradually peeling back the layers and forging connections with your inner world in a way that makes sense to you. Some days will be easier than others. Sometimes you’ll identify a feeling and other times you’ll still be stumped – and that’s okay. What matters is that you are engaging in the process of understanding yourself better, which is a lifelong skill that will serve you in many areas of life.

In conclusion, living with AuDHD and alexithymia means navigating a unique emotional landscape. It comes with challenges, yes, but also with the potential for deep self-discovery and growth. By recognizing alexithymia as the separate co-traveler it is, neurodivergent adults can seek out the right support and strategies – from body-based awareness to creative communication – to bridge the gap between having feelings and understanding them. It’s like learning a new language, the language of your own emotions, and with patience and practice, you will become more fluent. In the meantime, be gentle with yourself. You’re not alone on this path, and each small step you take is lighting a candle in what once felt like the dark. Emotions may not come with subtitles, but you are gradually writing your own guidebook to them – one honest effort at a time.

Paid Add-On: The Emotion Translation Toolkit (AuDHD + Alexithymia Edition)

Turn “I don’t know how I feel” into data you can use.

This is a mini-pack + guided audio + templates designed for neurodivergent adults who feel emotions like weather systems: real, intense, and weirdly unnamed.

What this paid add-on helps with

Catching feelings before they become a meltdown, shutdown, rage spiral, or “why am I crying at 11:47pm”

Translating body signals → emotion guesses → actual needs

Communicating with people without needing to magically become an emotions poet overnight

Building emotional awareness in a way that doesn’t rely on “just sit quietly and identify your feelings” (LOL)