Breaking the Silence on ADHD

Understanding, Science, and Self-Advocacy

Talking about ADHD can feel like walking a tightrope. You know in your gut that your difficulties aren’t a moral failing or “just an excuse,” but society’s stigma and your own shame can make it hard to say the words aloud. Maybe you’ve kept your diagnosis secret at work, or stayed silent when a friend quips “you’re just lazy” after you miss a deadline. These internal struggles—negative self-talk, guilt, worry about disappointing others—are a common part of the ADHD experience.

Over time, hearing people blame you for forgetfulness or impulsivity can erode confidence and make you feel ashamed or “broken.” This is confirmed by research: frequent reminders of unmet expectations often snowball into internalized shame for people with ADHD. In fact, stigma around ADHD has been shown to lower self-esteem and self-efficacy, making us less likely to advocate for ourselves. Underneath it all, many ADHDers know the truth: we’re not being difficult on purpose. We’re often working twice as hard just to appear “normal,” and when we falter, we beat ourselves up.

This self-criticism is understandable but unkind. The reality is that we live with an invisible neurodevelopmental disorder, so others often think we’re just like everyone else – they assume we “should” remember things or focus when we can’t. When people around you don’t understand ADHD or fail to offer support (for example, not giving reminders or accommodations), it’s easy to feel isolated and overwhelmed. Such negative responses can reinforce harmful beliefs, like “I’m careless” or “I’ll never get this right,” which in turn fuel more shame. But none of this reflects your worth or effort. In fact, experts stress that feeling shame over ADHD is very common – almost every person with ADHD will experience it at some point. It’s the stigma talking, not the truth.

It helps to remember that ADHD isn’t a character flaw. It’s a real, brain-based condition. Many ADHDers have internalized society’s message that we should “just try harder,” but as one psychiatrist notes, ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder – an invisible brain wiring issue – not laziness. Decades of neuroscience show our brains develop and function differently: it often literally takes more effort for our brains to organize tasks, filter out distractions, or keep track of time. Imagine trying to herd squirrels through an obstacle course – exhausting and unpredictable. When we let ourselves take that perspective (ADHD is how our brains work, not who we are), we can be kinder to ourselves. Over time, working through that shame – with self-compassion and support – is key to moving forward.

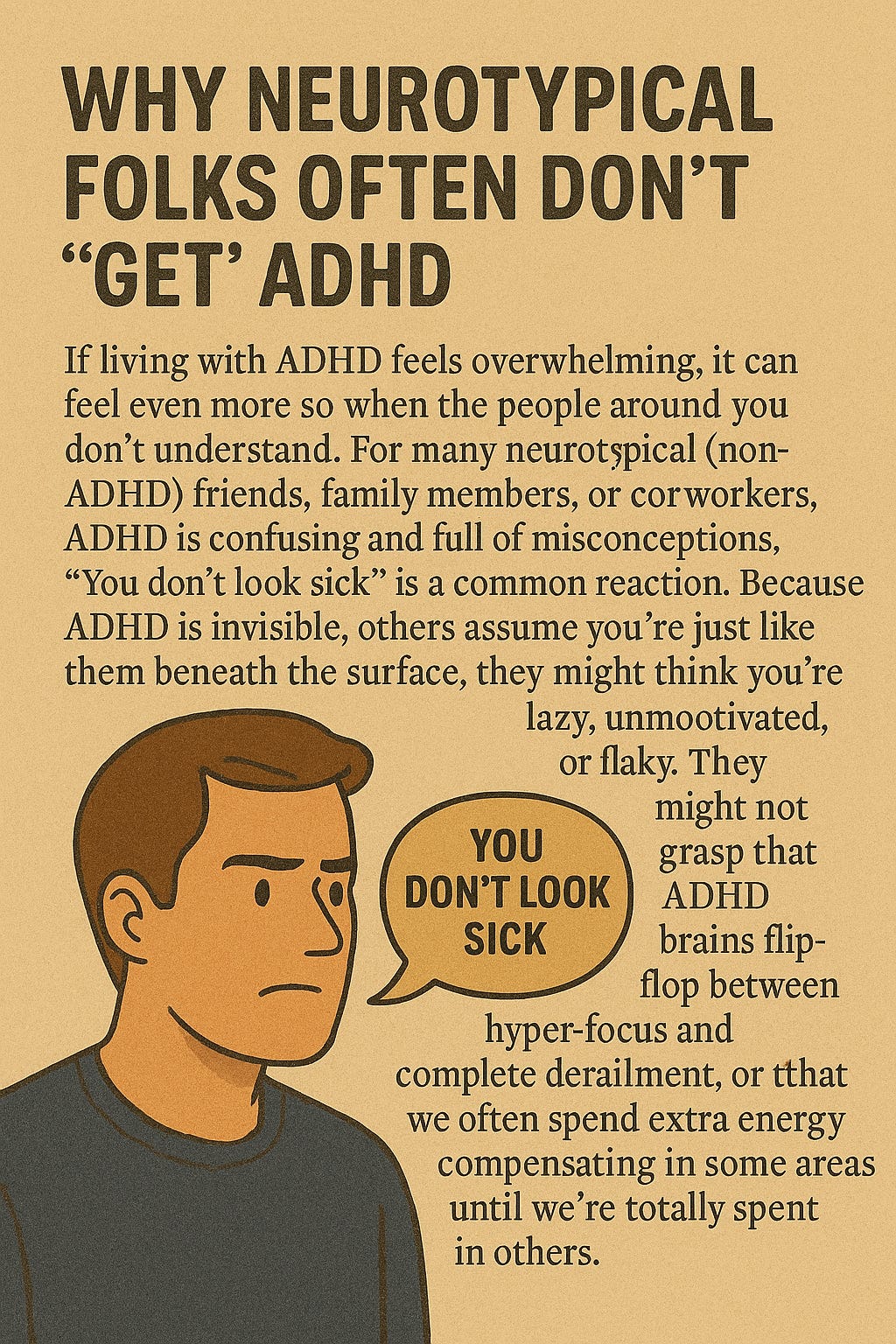

Why Neurotypical Folks Often Don’t “Get” ADHD

If living with ADHD feels overwhelming, it can feel even more so when the people around you don’t understand. For many neurotypical (non-ADHD) friends, family members, or coworkers, ADHD is confusing and full of misconceptions. “You don’t look sick” is a common reaction. Because ADHD is invisible, others assume you’re just like them beneath the surface. When they see you easily focus on something hyper-interesting (like a video game or movie) but struggle in class or at the meeting, they might think you’re lazy, unmotivated, or flaky. They might not grasp that ADHD brains flip-flop between hyper-focus and complete derailment, or that we often spend extra energy compensating in some areas until we’re totally spent in others.

A big reason for misunderstanding is that many people still think of ADHD as “just in kids” or only about hyperactive boys. In reality, ADHD almost always starts in childhood but often carries into adulthood – roughly 75% of children with ADHD continue to have significant symptoms as adults. The symptoms may change (maybe the overt hyperactivity calms down into inner restlessness) but the core attention and impulse challenges remain. Also, because boys are diagnosed more often, girls and women with ADHD are frequently missed. (Statistics show boys are diagnosed about three times more often than girls!) This means many loved ones might think “how could she have ADHD if she’s quiet and organized sometimes?” or “he can concentrate on games, so he can’t be distracted at work.” These assumptions ignore ADHD’s hidden flips and flips between strengths and blind spots.

Another misconception is that ADHD is just behavioral – that we could snap out of it if we wanted to. But neuroimaging tells us otherwise. The ADHD brain is literally wired differently. Key brain regions (especially the prefrontal cortex, which acts like a CEO for attention and impulse control) often have weaker connectivity or take longer to mature in ADHD. Neurotransmitters like dopamine (the “motivation” chemical) are usually lower in key reward areas. In practice, this means that what feels effortless to others (like waiting quietly, following a routine, or picturing a deadline) can feel like slogging through mud to us. Because these differences are internal, people don’t see them, and may chalk up our struggles to personal failings.

Finally, ADHD’s invisibility can breed judgment. Someone might say “I have a short attention span too,” misunderstanding that with ADHD your brain’s internal clock is off or working memory is weaker by default. It can be hard for them to empathize when they can’t see the struggle. In short, the world often expects us to behave like neurotypical brains even though ADHD is a recognized disability – and when we inevitably drop the ball on some tasks, we get labeled “messy” or “irresponsible” instead of understood. This gap in understanding can make an ADHDer feel like an outsider, even among loved ones.

Inside the ADHD Brain: Science of Focus, Time, and Emotions

To bridge this gap, it helps to know what’s actually happening in our brains. ADHD is a neurobiology story as much as a personal one. Imagine your prefrontal cortex as the “project manager” area of the brain that plans, organizes, and holds information in mind. In ADHD, this part of the brain tends to have weaker activity and connectivity. This explains why executive functions – like planning steps, filtering distractions, and remembering instructions – are often challenging. For example, working memory (the brain’s scratch pad) is commonly impaired. Studies find that most kids (and many adults) with ADHD have measurable deficits in their working memory. It’s as if the sticky-note pile on our project manager desk always falls over.

Another key player is the brain’s reward pathway, heavily driven by dopamine. In ADHD this pathway often operates below the typical level. Brain scans of unmedicated adults with ADHD show lower-than-normal levels of dopamine markers in areas like the nucleus accumbens (the brain’s “feel-good” hub). Clinicians speculate that this blunted reward response makes everyday tasks (work reports, chores, studying) feel less intrinsically motivating. Put simply, if the brain’s “you’ll love finishing this task!” signal is weak, procrastination and distractibility can easily win out. This is why stimulant medications (which boost dopamine) often make people with ADHD feel calmer and more motivated. It also explains the so-called “high time-preference” or “time-blindness” some ADHDers experience: because future rewards feel distant, the present moment’s pull is stronger.

Speaking of time, another hallmark is time blindness. Many people with ADHD have a warped sense of time passing. Five minutes might feel like fifty, or vice versa. A simple task can mysteriously suck hours, leaving us stunned, or we can find ourselves suddenly late with no idea how. Occupational therapy experts even call time-perception issues a critical executive function in ADHD. This neurological quirk means we often misjudge deadlines or fail to break projects into steps, contributing to chronic lateness or rushing at the last minute.

Emotional regulation is another brain-based challenge. Contrary to the old “just hyperactive” stereotype, many people with ADHD have strong emotions that swing quickly. Research finds that substantial numbers of adults with ADHD (roughly one-third to two-thirds, depending on how you measure it) experience significant difficulty managing emotions. We might get easily frustrated or have intense reactions that feel overwhelming. Part of this is due to the prefrontal cortex’s role in controlling impulses – when it’s underactive, it’s harder to throttle anger or excitement. Studies show ADHD brains also tend to favor quick, small rewards (an immediate comment or treat) over larger delayed ones, which ties back to that dopamine story. All of this science is not to make excuses, but to explain the why: our brains are wired in a way that affects our motivation, memory, time-keeping, and emotions.

Understanding the science doesn’t just justify our struggles – it can empower us. It reminds us that things like being forgetful or needing extra stimulation aren’t character flaws but brain differences. It’s like knowing there’s a physiological reason you feel tired – it’s easier to address it than to blame yourself. And importantly, this knowledge can guide strategies: if ADHD brains are reward-hungry and time-blind, we can use timers, immediate rewards, and structured routines to build workarounds. If we know our emotional brake is a bit weak, we can practice coping skills or seek therapy focusing on emotion regulation.

Finding Your Voice: Practical Advocacy and Boundaries

Knowledge is empowering, but it’s only part of the journey. Many of us struggle with how to bring up ADHD in everyday life – with friends, teachers, or bosses – without feeling like we’re begging for excuses. The key is framing and self-confidence. Remember: you are the expert on your experience. Nobody else feels your struggles first-hand. Here are some practical tips, couched in a supportive, forward-focused spirit, for talking about your ADHD:

Start with the positive and personal. You might say, “I’ve been learning more about my brain and I discovered I have ADHD. It means I have some strengths – like being very creative – but also some challenges.” This kind of gentle framing (neurodevelopmental fact plus personal insight) helps people listen. One ADHD guide suggests beginning conversations by clarifying that “ADHD is something that happens in your brain – you can’t control whether you have it or not”. Emphasize it’s not a choice or a flaw.

Use “I” statements and examples. For instance: “I’ve noticed that my brain doesn’t track time the way others expect. I genuinely want to meet deadlines, but I often lose track of time. This is part of how my ADHD works.” Concrete examples (like “I stayed up too late finishing a project because I lost track of time”) make it relatable. You could borrow an analogy or phrase: another person with ADHD found the “forest vs. map” metaphor useful – it’s like being in an unpredictable forest without a map. Ultimately, you’re explaining your reality, not asking for pity.

Set helpful boundaries or accommodations calmly. It’s okay to assert your needs in a non-confrontational way. For example, in the workplace you might say, “I focus best with fewer interruptions – could we try scheduled check-ins instead of popping by unexpectedly?” With friends, you could say, “Sometimes I need a quiet 10-minute break after social events to recharge, it’s not personal.” These statements are not excuses but honest requests. Research and disability advocates encourage clarifying limits: clear boundaries actually improve relationships by letting others know how to support you.

Educate as needed, but pick your moments. Sometimes a quick fact is helpful: “ADHD affects about 4% of adults and is recognized by the DSM-5. It’s like a learning disability for life skills.” Sharing a sentence from an article (like that it’s neurobiological) can lend weight. However, gauge your audience. Close friends or family might appreciate a longer conversation; strangers or casual acquaintances probably do not need a lecture.

Build your support system. Find people who do listen. Maybe a coworker has ADHD or a therapist or a friend who’s read about neurodiversity. Opening up to one understanding person can be liberating and reduce shame. Support groups (online or local) are great outlets where no explanation is needed – everyone gets it.

Practice self-advocacy as an ongoing skill. This means knowing your ADHD profile (your “strengths and weak spots”) and openly communicating it. It also means reminding yourself that you deserve understanding. You have as much right to struggle with mental processes as a short person has with reaching a shelf. Over time, you’ll gain confidence: every time you explain, you chip away at the stigma.

Remember: talking about ADHD is not about making excuses; it’s about bridging understanding. It lets people see where your challenges come from, and often they’ll respond with more patience and help once they do. For instance, a manager might grant a deadline extension, or a friend might send a reminder text, once they see your brain’s perspective. You are simply seeking a level playing field, not special treatment.

It also helps to reframe internally: saying the words out loud can be empowering. Instead of thinking “I’m a failure because of ADHD,” try “ADHD is part of me, and I’m working on it.” Affirmations can be as simple as, “I’m not lazy, I just need different strategies.” Studies suggest that viewing ADHD in a positive, empowered light reduces shame. Keep learning and talking, celebrate small wins (like that time you did remember!), and be gentle with yourself.

Bottom line: ADHD is not an excuse but an explanation – a roadmap to understanding your brain. Knowledge, self-compassion, and the right words can help you share that map with others. By advocating for yourself (and setting clear boundaries), you not only lessen the burden of shame, but you also invite collaboration and empathy. Over time, every conversation you have about ADHD chips away at stigma – both in your own mind and in the world around you.

Sources

PsychCentral (2021). “Coping with Shame When You Have ADHD”.

Brookhaven National Laboratory News (2009). “Deficits in the Brain’s Reward System Observed in ADHD Patients”.

OccupationalTherapy.com (2025). “Time Blindness: A Critical Executive Function in Adults with ADHD”.

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of ADHD: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Cortex (J Pediatr).

Kasper et al. (2019). Working Memory and Short-Term Memory Deficits in ADHD (Front Hum Neurosci).

Surman et al. (2013). Emotion Dysregulation in ADHD (J Clin Psychiatry).

TalkWithFrida (2023). “Talking to Friends and Loved Ones About ADHD”.

Full Well Therapy (2020). “ADHD: Coping with an Invisible Disability”.

Shimmer ADHD Coaching (2023). “Empowering Self-Advocacy for ADHD”