Navigating Task Switching with AuDHD: Challenges, Strategies, and Tips

AuDHD and Task Switching: Challenges, Strategies, and Supportive Prompts

AuDHD – a term for co-occurring autism and ADHD – can make the simple act of switching tasks feel incredibly daunting. If you find that moving from one task to another is like pulling teeth, you’re not alone. Autistic and ADHD brains are wired differently, and many of us with these neurotypes have an extremely tough time with task switching. In daily life and professional settings, where demands pile up and changes come quickly, struggling to “change gears” can lead to stress, frustration, and feelings of overwhelm. The good news is that understanding the neuroscience behind this struggle can help in developing strategies to cope. This comprehensive guide will delve into why task switching is challenging for AuDHD adults, and offer practical tips (plus some self-coaching journal prompts) to make those transitions a bit smoother – all in a relatable, no-nonsense tone.

Understanding AuDHD and Task Switching

What is AuDHD? “AuDHD” isn’t a formal diagnosis, but a popular way to describe someone who is both autistic (Au) and has ADHD (DHD). Research has found a significant overlap between autism and ADHD – by some estimates, around 40-70% of autistic people also have ADHD, and conversely a large percentage of people with ADHD are also autistic. So if you identify with both neurotypes, you’re far from a rarity. However, living with both can be a unique balancing act. Autism and ADHD traits can sometimes conflict with each other – for example, the autistic desire for routine and predictability versus the ADHD craving for novelty. This internal tug-of-war can make certain challenges (like task switching) even more pronounced.

What do we mean by “task switching”? In plain terms, task switching is the ability to shift your focus and effort from one task to another. It sounds straightforward, but it’s actually a complex executive function that relies on cognitive flexibility. Think of your brain as having an internal gear shift: you have to mentally “turn off” the current task and “turn on” a different task. For most neurotypical people, this gear shift is relatively smooth – they can adapt and transition with only mild annoyance. But for neurodivergent folks (especially those with ADHD, autism, or both), that mental gear shift can grind and stall. In fact, one psychologist quips that our brains often have “rusty on/off switches,” making it hard to smoothly disconnect from one activity and move to the next.

Why is task switching so hard with AuDHD? Both autism and ADHD contribute their own challenges here:

Autistic perspective: Autistic brains tend to hyper-focus on a narrower set of interests or tasks, a concept sometimes called monotropism (a tendency to fixate deeply on one thing at a time). This intense focus means that anything outside the current focus can feel nonexistent – autistic people might not notice other tasks or quickly forget them once they’re out of sight. Changing tasks requires shifting attention away from something that feels safe or absorbing, which can be jarring. Many autistic individuals also thrive on routine and predictability; an unexpected transition can create anxiety because it disrupts the anticipated sequence of events. Autistic advocates use the term “autistic inertia” to describe the difficulty in starting, stopping, or switching activities – essentially a tendency to stay stuck in the current state or task. It’s not stubbornness; it’s literally how the autistic brain manages (or struggles with) change.

ADHD perspective: ADHD, on the other hand, is often described as an interest-based nervous system. If a task isn’t stimulating or rewarding (i.e. not giving that dopamine hit), the ADHD brain has trouble engaging with it. Paradoxically, while ADHD is associated with distractibility, it also involves episodes of hyperfocus – getting so absorbed in one task that hours pass by. When an ADHDer is in hyperfocus, switching tasks is extra hard: you might not even register that something else needs your attention (like a phone ringing or a bodily need) because your brain is immersed. Stopping that hyperfocused task feels like slamming on mental brakes. Moreover, ADHD often comes with executive function deficits in areas like planning, working memory, and impulse control. If you have ADHD, you might struggle to plan ahead for the next task or hold in mind what you were about to do, which makes switching tasks a bit like walking into a fog – you forget where you were going. In fact, research suggests that difficulties with task switching in ADHD are linked to features of inattention, where you don’t pre-plan the next steps and instead react to whatever is grabbing your attention in the moment.

The AuDHD combination: Now, imagine having both of these dynamics at play. You may have an autistic side that craves consistency and can zero in on one thing for hours, and an ADHD side that seeks novelty and gets easily sidetracked. It’s like driving a car with one foot on the brake and one on the gas. One part of you hates being interrupted or changing routine, while another part of you gets bored and ping-pongs between ideas. No wonder task switching with AuDHD can be so fraught! As one psychologist notes, this mix of traits can “defy common notions” of each condition – e.g. feeling restless yet overwhelmed by change at the same time. It often leads to internal confusion (“Why am I like this?”) until you realize both neurotypes are in the mix. The important takeaway is that difficulty switching tasks is not a character flaw – it’s a reflection of how your unique brain operates. Next, let’s look a bit more at what’s happening in the brain during these moments.

The Neuroscience Behind Task Switching Difficulties

It’s one thing to describe the experience, but what’s actually going on in our brains that makes task switching so tough for AuDHDers? The answer lies in executive function networks – the systems in our brain (largely front and center in the prefrontal cortex) that handle planning, decision-making, and shifting attention. In both autism and ADHD, these executive circuits can operate differently than in neurotypical brains.

For individuals with ADHD, studies have shown differences in the brain’s neurotransmitter systems (like dopamine) and in activation of frontal brain regions. These differences contribute to the classic ADHD symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity – and the very same neurological factors also make task switching difficult. In essence, the ADHD brain can struggle to turn its attention off from the current task and on to the next one on command. This is why someone with ADHD might genuinely want to move on to that overdue report or household chore, but their brain’s “switch” feels stuck. You might have heard the term “task paralysis” – that’s what it feels like when you can’t shift gears or initiate the next activity, even if some part of you knows it’s time to do so. To an outside observer, it may look like laziness or procrastination, but in reality your brain’s goal-directed mechanisms are temporarily frozen by overwhelm or lack of executive sparkhealthline.comhealthline.com.

In autism, neuroscience points to differences in connectivity and information processing that favor deep, singular focus. One theory (monotropism) suggests the autistic brain tends to allocate resources heavily to a narrow interest, leaving fewer resources to attend to other things. So when an autistic person is engrossed in a task or a topic, their brain isn’t idly keeping track of other tasks in the periphery – meaning a sudden demand to switch tasks feels like a sharp derailment. Moreover, executive dysfunction in autism can manifest as difficulty with flexibility and switching attention. Brain imaging studies often find that tasks requiring quick set-shifting light up neurotypical brains in ways that autistic brains may not replicate as easily, indicating a difference in how the brain transitions from one “mode” to another.

To put it simply, our AuDHD brains need a longer loading time to shift context. Imagine a computer trying to close one heavy program and open another – if the processor isn’t optimized for multitasking, things will lag or even freeze for a bit. Many of us have “laggy” brain processors when it comes to task switching. It doesn’t help that both autism and ADHD often come with working memory weaknesses – the mental sticky note system that holds information briefly. If you struggle with working memory, you might find it hard to hold the new task instructions in mind while still wrapping up the old task. Or if you get interrupted, it’s like your brain drops what it was carrying; when you try to come back, the thought you were holding has vanished.

Lastly, there’s the factor of sensory and emotional regulation. Neurodivergent brains often experience sensory input and emotions more intensely. Transitioning from one task to another isn’t just a neutral action – it can provoke a spike of discomfort or anxiety (a mini fight-or-flight response saying “No, I don’t want to switch!”). Your brain might react to a task switch like it’s a sudden plunge into cold water. In fact, researchers and therapists note that unexpected transitions can be distressing and dysregulating, practically causing a stress response. Multiply that stress by the dozens of little transitions we face every day, and it’s no surprise that by evening, an AuDHD brain can be completely exhausted from all the gear-shifting. This brings us to how these challenges show up in everyday life.

Everyday Struggles and How It Feels

If all this talk of brain wiring still feels abstract, just think about some real-life scenarios:

You’re deeply focused on a work project, in the zone, when a coworker messages you about an unrelated issue – suddenly you’re expected to switch and respond. Your heart jumps; you feel irritation at the interruption and maybe freeze up trying to shift your thoughts. It’s as if your brain’s momentum was slammed into a wall. Later, you might find it hard to return to the original project with the same focus as before.

It’s a busy day and your to-do list has 10 different tasks. You know you need to start task B, but you’re still mentally stuck on task A (or just stuck in a void of not being able to start anything). The more you think about switching tasks – planning all the steps, anticipating the effort – the more overwhelmed you get. Eventually, you end up doing none of them and feel awful about it.

You were enjoying a hyperfocus session on a hobby (say, coding a personal project or organizing a collection) and lost track of time. Now it’s 1pm and you haven’t eaten, plus you’re late for an appointment. Transitioning out of that hyperfocus feels physically hard – you’re groggy, irritable, maybe on the verge of a meltdown because the outside world suddenly demands your engagement.

Sound familiar? These are everyday examples of how task switching difficulties can play out. Emotionally, it can be a rollercoaster. Many AuDHD folks report feeling frustrated, anxious, or even angry when forced to rapidly switch tasks. There’s a sense of internal panic or resentment: “Why can’t I have more time? I’m not ready to change what I’m doing!” Being asked to produce output on the fly, when your mind was elsewhere, can make you feel completely unprepared. Over time, this can erode your confidence – you might start to dread new tasks or avoid situations where quick switching is expected.

There’s also often a hefty dose of guilt or self-criticism. After struggling with a transition, you might think, “Why am I like this? Other people handle this fine. Am I just lazy or incapable?” Let’s bust that myth right now: you are not lazy. The struggle you experience is very real and rooted in your neurology. For example, what looks like “ignoring a responsibility” to someone else is usually task paralysis – a state of overwhelm where your brain’s ability to initiate or shift tasks is locked up. Autistic inertia and ADHD paralysis are internal battles, not a lack of willpower. Your desire to do the task is there, but the execution piece is misfiring. Recognizing this distinction is important for your self-esteem; it shifts the narrative from “I’m flawed” to “I have a challenge, and I might need support or new strategies.”

The cumulative effect of constant task-switching stress can be serious. Many neurodivergent adults report burnout when life demands push them into too many rapid transitions without recovery time. You might manage to appear “fine” on the outside, but internally you’re using double the effort to keep up with the bouncing tasks. Eventually, you crash – in burnout, even basic self-care tasks feel insurmountable. Alternatively, you might experience meltdowns or shutdowns: emotional tipping points where the brain says “Nope, I’m done” – cue tears, anger, or numb withdrawal. Understanding these outcomes isn’t meant to scare you, but to validate that task switching difficulty is a legitimate challenge with real impacts. It’s not “all in your head” in the dismissive sense – rather, it’s in your brain wiring, and it affects daily living in tangible ways.

For many adults with AuDHD, switching tasks is anything but simple. It can feel like your brain’s gears get jammed when you’re forced to abruptly change direction. In a busy office or a chaotic home environment, juggling multiple demands can quickly lead to mental overload. The stress of an impending transition might manifest as tension in your body, irritability, or even panic, as your mind struggles to detach from the current focus and reorient to something new. Over time, these repeated stressful transitions can make you apprehensive about changes and contribute to burnout. (Neurodivergent brains often react intensely to sudden task changes, which is why such moments can be so overwhelming.)

Now that we’ve painted a (perhaps intimately familiar) picture of the struggle, let’s shift to a more hopeful note: What can you do about it?

While we can’t rewire our brains overnight, we can adopt tools and strategies that work with our neurodivergent brains, not against them. In the next section, we’ll cover practical tips to ease task transitions, drawn from both scientific understanding and lived experience.

Tips and Strategies to Manage Task Switching Difficulties

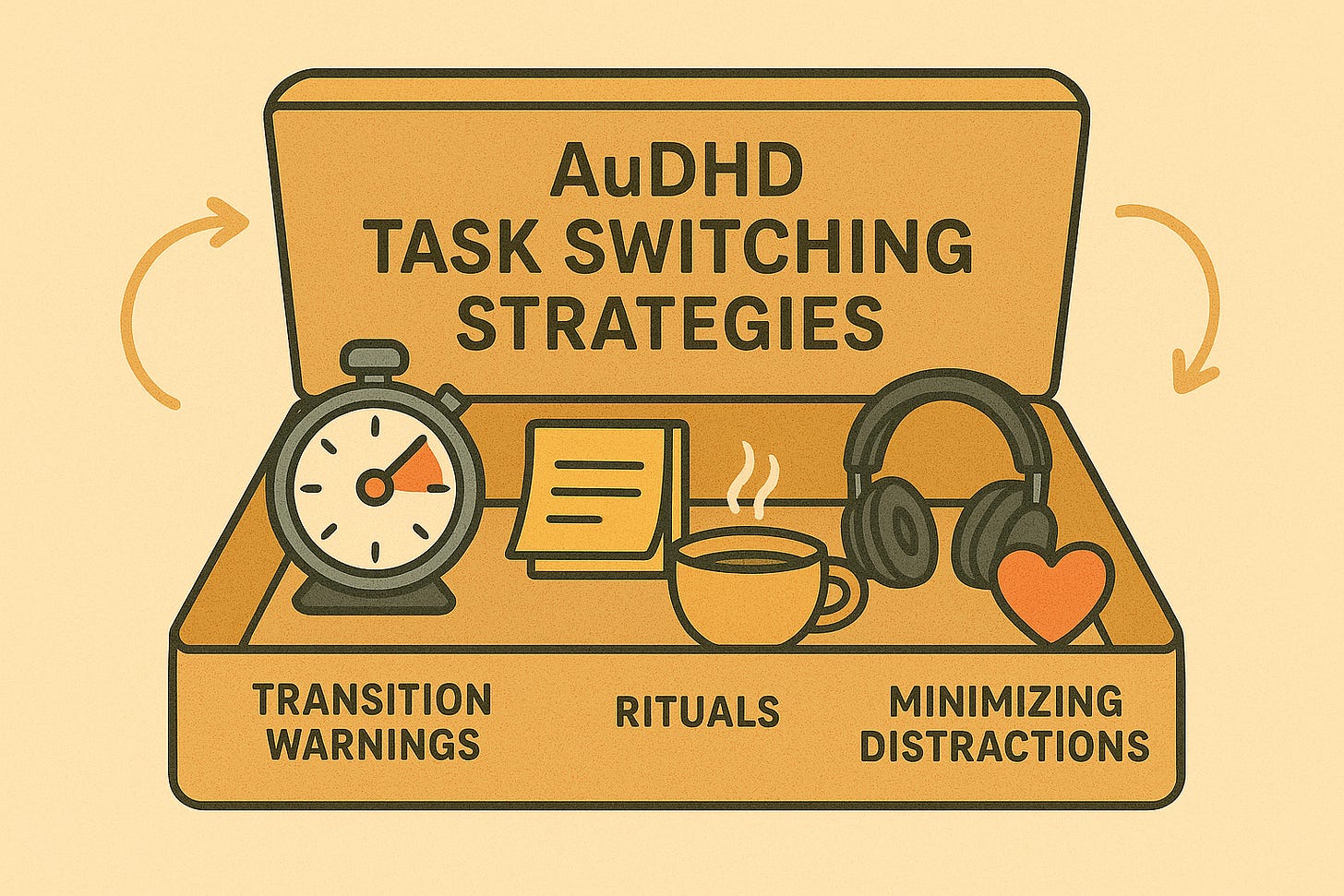

Improving task switching is all about finding tricks and supports that work with your unique brain wiring instead of fighting it. Every AuDHD individual is different, so think of these strategies as a toolbox – experiment with them and keep what resonates. The goal isn’t to become a multitasking superhero; it’s to reduce stress and feel a bit more in control of your day. Here are some strategies to consider:

Use Visual Schedules and Lists: Our brains often handle visual information better than just mental notes. Try laying out your tasks in a visual format – a whiteboard, a color-coded to-do list, a digital kanban board, whatever works. Seeing the sequence of tasks can prepare your mind for upcoming transitions. For instance, a visual schedule (even a simple list with numbered tasks or time blocks) provides a clear roadmap of your day, helping you mentally brace for switching ahead of time. At work, this might mean writing down your top 3 priorities for the day and literally checking them off and rewriting the list when you move to the next batch.

Give Transition Warnings (Even to Yourself): Sudden switches are the hardest. Whenever possible, build in warnings before a change. If you have control over your schedule, set alarms or timers as gentle signals that a transition is coming up. For example, if you need to leave for an appointment at 3:00, set an alarm at 2:50 to start wrapping up your current task. If you struggle to pull away from hyperfocus, consider using a timer that vibrates or a smart lamp that changes color – any cue that cuts through your tunnel vision. The idea is to mimic the helpful prompts a teacher might use for a child (“Five more minutes on this activity, then we clean up”) – except you’re giving yourself those prompts. Gradual transitions tend to be less jarring, so a two-step process (warning, then switch) can ease the mental whiplash.

Build Buffer Time Between Tasks: One of the simplest but most effective accommodations you can give yourself is padding between tasks. If you think a task will take 30 minutes, schedule 40 or 45 so you have a cushion to wind down and switch. Rushing directly from Task A to Task B is a recipe for overload. Instead, treat the time in between as its own mini-task: a breathing space to stretch, walk, get water, or just do nothing for a few minutes. This buffer acknowledges that your brain might need extra time to disengage and then re-engage. In practice, if you have back-to-back meetings or responsibilities, see if you can end things a bit early or start a bit late to create a margin. Even a 5-minute buffer (where you literally do a reset ritual like closing your eyes and taking deep breaths) can help. It’s during this buffer that you might also use the transition warning techniques above. Planning your day with these margins will make the whole flow more forgiving and less anxious.

Chunk Tasks into Smaller Steps: Big, amorphous tasks are the enemy of smooth transitions. When a task is too large, we’re more likely to get stuck (because where do we even start?) or to dread switching to it (because it feels like jumping into an ocean). Combat this by breaking tasks down into bite-sized chunks. Instead of “Write report,” your chunks might be: “Outline report sections,” “Draft introduction,” “Create 3 data charts,” etc. Each chunk should feel manageable. The reason this helps with task switching is twofold: (1) Finishing a small sub-task gives you a hit of accomplishment, which makes it easier to pause and switch (you feel like you’ve completed something, rather than being interrupted mid-way through a colossal task). (2) When you return to the project later, you know exactly what piece to tackle next, rather than holding a complex web of unfinished aspects in your head. This reduces the mental load when switching away and back again. So, whenever you feel overwhelmed by a task, step back and list its components. Tackle them one by one, and give yourself permission to switch to something else once a piece is done. You’re not “quitting” the task, you’re just moving in stages.

Establish Consistent Routines: Routines are like an autopilot for transitions. If your day follows a fairly set pattern, your brain can learn to anticipate and handle regular switches better because they’re part of a predictable script. For example, having a morning routine to start your day and an evening routine to wind down can bookmark your work and rest times, making those big transitions less chaotic. At work, maybe you always spend the first 30 minutes checking emails, or after lunch you do a quick review of your to-do list. By creating consistency, you reduce the number of unexpected transitions. Of course, life isn’t always predictable, but even small anchors (like a habitual coffee break at 3pm or a few minutes of planning every morning) can give a sense of stability. Just be careful to balance routine with variety in a way that suits both your autistic and ADHD sides – you might keep the structure the same while varying the content to prevent boredom (e.g., routine of reading for 30 mins daily, but a different book/topic each day).

Use Transition Rituals: A transition ritual is a short, intentional activity that helps signal your brain that one task is ending and another is beginning. This could be as simple as closing your laptop and tidying your desk for five minutes when you finish work, to symbolically “close out” that session. Or it could be making a cup of tea between tasks, doing a few stretches, or stepping outside for a moment of fresh air. The key is to choose something that helps you reset. For some, playing a specific 2-minute song and allowing yourself to jam out can release the tension of switching. Others might use mindfulness techniques, like a brief meditation or just consciously noting “I am letting go of Task A; I am now starting Task B” to self-cue the change. These rituals act as a bridge, giving your brain time to adjust. Over time, your brain will start to associate the ritual with a state of flux, which can make transitions feel a bit more natural.

Minimize External Distractions: It’s much harder to switch tasks intentionally when you’re constantly battling involuntary switches (like getting distracted). Reducing distraction isn’t always fully possible, but do what you can to create a transition-friendly environment. That might mean using tools to block notifications or interruptions during deep work, wearing noise-cancelling headphones if noise pulls you away, or keeping your workspace organized so that random objects don’t steal your attention. The idea is to protect your focus on the current task until you choose to switch. And when you do choose, try to ensure the next task’s environment is also distraction-calm at least for the first few minutes, so you can ramp up into it. For example, if you need to switch to a task that requires concentration, close unrelated tabs and clear your desk beforehand. Fewer shiny things vying for your attention means your executive brain can concentrate on the primary switch at hand.

Leverage Supports and Accountability: Sometimes, an external nudge can help a ton. Body doubling is a popular ADHD strategy where you do tasks in the presence of someone else (they don’t have to help; their mere presence can keep you on track). Having a colleague, friend, or an accountability partner aware of what you’re supposed to be doing can gently pressure your brain to switch when you need to. For example, telling a coworker “I’m going to spend one hour on task X, then I’ll switch to task Y” creates a commitment device. If you struggle to start a task, consider asking a friend to stay on a video call with you while you both work on your own tasks – the social presence can kick-start your initiation. According to one counseling team, working with a friend or partner on tasks is a valid strategy to overcome inertia. You can also link up new tasks with existing routines (e.g., always do a quick kitchen clean right after dinner, making it a paired activity), so that the momentum of one carries you into the next. And if you’re really stuck, don’t be ashamed to ask for help to get started – sometimes just having someone else outline the first step or do it with you is enough to break the inertia and get you switching to the necessary task.

Practice Mindfulness and Self-Compassion: This might sound a bit abstract compared to the other tips, but training yourself in mindfulness techniques can improve your awareness of when your mind is getting stuck or resistant, which in turn can help you gently guide it through a transition. Mindfulness could be as simple as taking a slow, deep breath and noticing “I feel anxious about stopping this task; that’s okay.” By acknowledging the feeling without judgment, you may rob it of some power. Another aspect here is self-talk – instead of “I have to switch now or else,” try a compassionate tone: “It’s hard to switch tasks, I know. Let’s just take it step by step.” Some people find it helpful to visualize the tasks: imagine closing one tab in your mind and opening another, or picture yourself setting down one hat and putting on another role’s hat. It sounds silly, but little mental exercises like this can make the process feel more tangible and under your control. Above all, practice forgiving yourself on the days that switching tasks doesn’t go well. We all have those days when our brains just refuse to cooperate. Beating yourself up will only add stress; instead, treat yourself like you would a friend – with understanding and patience.

Consider Professional Help and (If Needed) Medication: Finally, remember that you’re not the first person to face these challenges, and there are professionals who specialize in neurodivergent coaching and therapy. An executive function coach or therapist can work with you to develop personalized strategies and accountability systems. They can also help you address related issues like anxiety management, which often goes hand-in-hand with task overwhelm. If your task switching problems are severely impacting your life, it might be worth discussing with a medical professional, because ADHD medications or other treatments can sometimes make a big difference. Many ADHD adults describe feeling a profound change when they first tried appropriate medication – as one person put it, “for the first time, I could gracefully dart from subject to subject when needed”. Medication can “grease” those rusty switches, so to speak, making it easier to shift focus. Of course, medication is a personal choice and not suitable for everyone, but it’s one potential tool in the toolbox. Whether or not you go that route, never hesitate to seek support. You deserve understanding and help, not skepticism, when it comes to these challenges.

By implementing some of these strategies, you’re essentially creating a more neurodivergent-friendly workflow for yourself. Remember, small changes add up. Even mastering one or two of these tips can significantly reduce daily stress. Celebrate your wins – every time you successfully switch tasks (even if it’s a bit messy), give yourself credit. And if something isn’t working, it’s not a failure; it’s valuable data about what doesn’t suit you, nudging you to try a different approach.

Journal Prompts for Self-Coaching and Mindfulness

One powerful way to develop better task-switching habits (and a kinder mindset around them) is through journaling. Writing things down can clarify thoughts, reveal patterns, and reinforce what you’re learning. Below are some journal prompts to help you reflect on your task switching experiences and coach yourself toward improvement. Try picking one or two that resonate and write out your answers. Be honest and gentle with yourself – this exercise is about understanding and growth, not judgment.

Prompt 1 – Reflect on a Recent Transition: Think of a specific time recently when you struggled to switch from one task to another. What was the situation, and how did you feel during that moment of transition? Describe what thoughts went through your mind and how your body felt. For example, did you feel anxious tightness, frustration, relief, confusion? Simply observing and describing this experience will help you become more mindful of what’s happening the next time a transition comes up.

Prompt 2 – Identify Your Triggers: What factors tend to make task switching harder for you? Is it certain times of day, certain types of tasks, physical sensations like hunger or fatigue, or maybe external distractions? List out some things you suspect contribute to your task switching difficulties. Then, for each trigger, jot down one possible adjustment. (For instance, “I struggle to switch tasks mid-morning because I’m hungry – maybe I need a better breakfast or a 10am snack break.”) This is a self-coaching exercise to preempt challenges before they knock you off course.

Prompt 3 – Envision a Smooth Transition: Recall or imagine a time when you successfully switched tasks with minimal stress. What did that feel like? What was different about that scenario – did you use any strategies (even unknowingly) that helped, such as taking a break or having clear instructions? Write about what an ideal, smooth task transition looks like for you. This can help you pinpoint helpful conditions to replicate. (E.g., “When I transitioned well, I noticed I had a clear plan for the next task and wasn’t rushing.”)

Prompt 4 – Plan a Transition Ritual: Based on what you’ve read and know about yourself, design a personal transition ritual and write it down in detail. It could be as simple as: “After finishing any task, I will stand up, stretch for one minute, and take three deep breaths before I start the next.” Make it something realistic and appealing to you. Journal about why you chose those elements and how you hope this ritual will help your brain. This solidifies your commitment and mentally prepares you to actually use the ritual.

Prompt 5 – Self-Compassion Letter: Take a moment to write a short, encouraging note to yourself about task switching. Pretend you are a compassionate coach or friend. Acknowledge that this is a real challenge (“I know switching tasks is hard for you and it often makes you feel overwhelmed”) and offer some kind words or advice to help ease the burden (“Remember, it’s okay to take your time. You are doing your best, and it’s not your fault your brain resists changing focus. You’ve put systems in place and you’ll keep improving with practice.”). This might feel awkward, but it’s a powerful way to reinforce a positive, understanding inner voice. You can revisit this letter whenever you’re feeling down on yourself for struggling.

By exploring these prompts, you’ll gain insights into your own patterns and needs. Over time, journaling can reveal how far you’ve come – maybe you’ll notice that what used to throw you into a panic is now manageable with the right routine, or you’ll catch that your mindset has shifted from self-blame to problem-solving. That’s huge progress!

Podcast Suggestion:

In conclusion, living with AuDHD in a fast-paced, ever-changing world isn’t easy. Task switching will probably always demand a bit more effort from you than from a neurotypical person – but with understanding, tools, and self-compassion, it can get easier. Remember that your brain has amazing strengths (creativity, hyperfocus, unique problem-solving, just to name a few) that come hand-in-hand with these challenges. Be patient with yourself. Implement changes gradually, celebrate small victories, and don’t be afraid to seek support where needed. You aren’t alone in this struggle, and you aren’t “broken” for experiencing it. With the right strategies and mindset, you can navigate task switching more smoothly and reduce the toll it takes on you, freeing up more of your energy for the things that matter. Here’s to working with our brains – quirks and all – and crafting a life workflow that respects our neurodivergent needs. You’ve got this!

Sources:

Healthline – ADHD and Task Switching: 10 Tips for Improvementhealthline.comhealthline.comhealthline.comhealthline.comhealthline.com

NeuroSpark Health – Task Switching and ADHD: Examples, How it Feels, and What to Doneurosparkhealth.comneurosparkhealth.comneurosparkhealth.comneurosparkhealth.comneurosparkhealth.comneurosparkhealth.comneurosparkhealth.com

Earth Coaching – Navigating Transitions: Task-switching Tips for ADHD, AuDHD and Autistic Folksearthcoaching.netearthcoaching.netearthcoaching.netearthcoaching.netearthcoaching.net

Well Roots Counseling – Understanding Autistic Inertiawellrootscounseling.comwellrootscounseling.comwellrootscounseling.com

Autism Parenting Magazine – Autism Monotropism: Understanding Focus and Attentionautismparentingmagazine.com

LA Concierge Psychologist – The Unique Experience of AuDHDlaconciergepsychologist.comlaconciergepsychologist.comlaconciergepsychologist.com

Verywell Mind – AuDHD: When Autism and ADHD Co-Occurverywellmind.com

Focus Bear Blog – ADHD Context Switching: Strategies for Smoother Transition