Why Time Feels Weird: Understanding Temporal Processing in AuDHD Brains

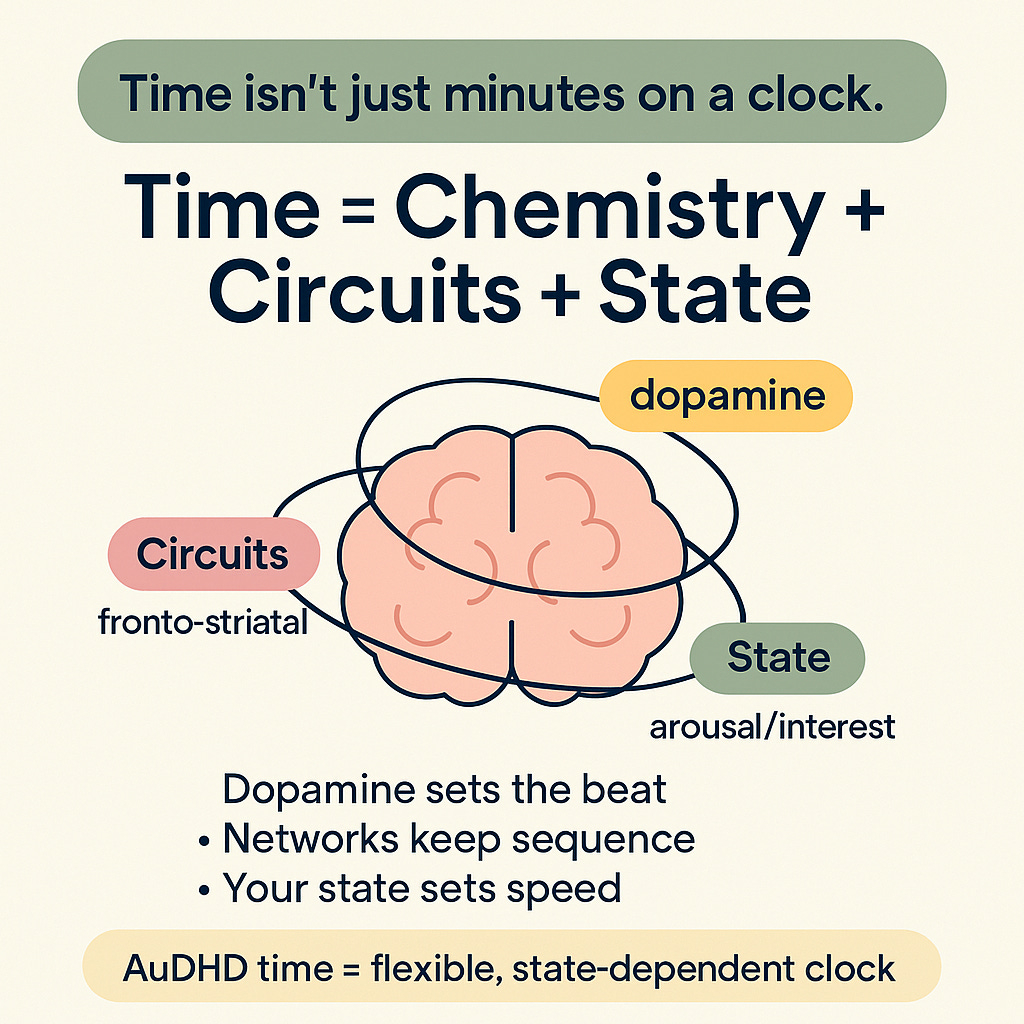

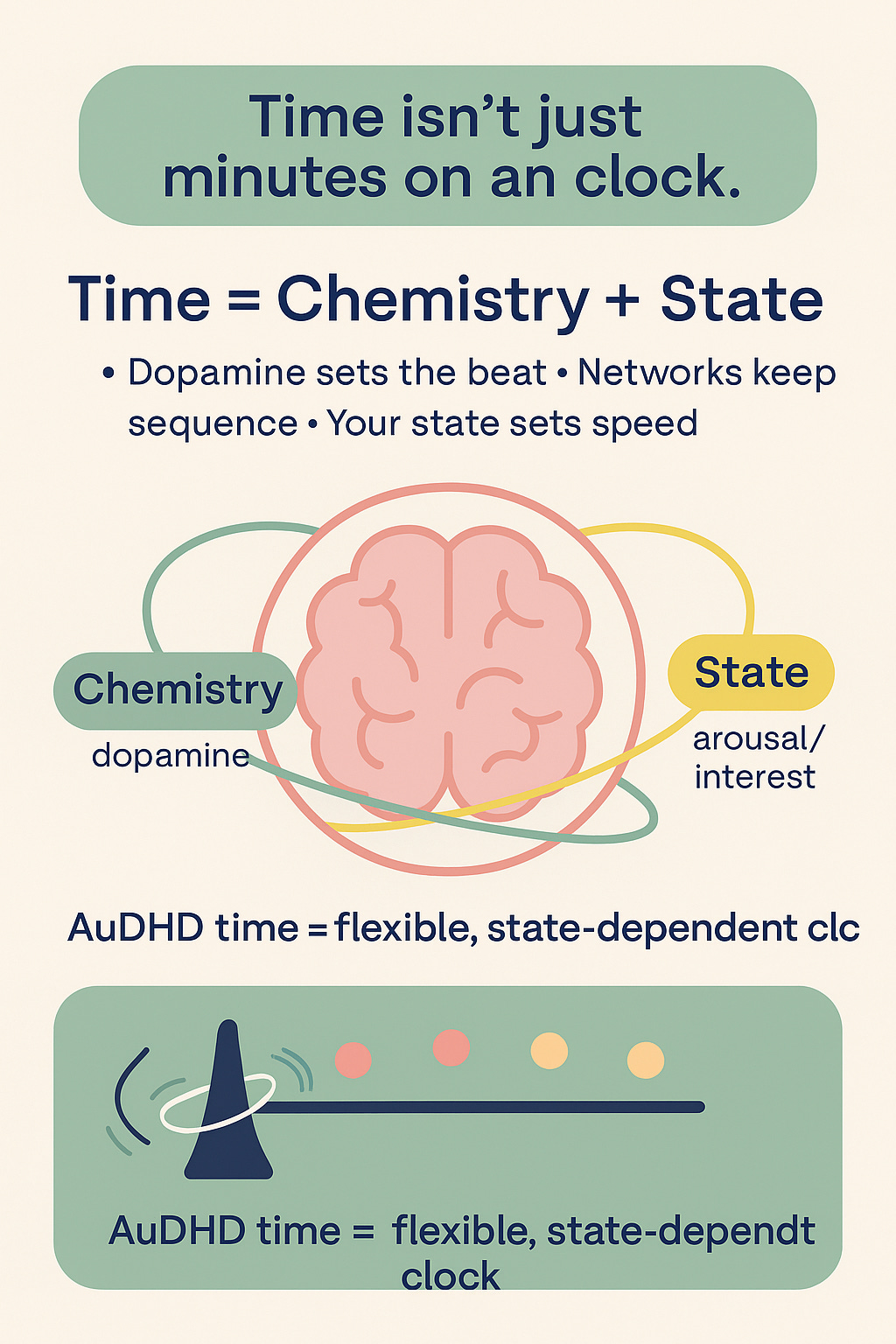

Time Isn’t Just “Minutes on a Clock” for AuDHD Brains – It’s Chemistry, Circuits, and State

Ever told yourself “I’ll do that in 5 minutes,” only to blink and suddenly an hour flew by?

Or sat through a 10-minute wait that felt like an eternity?

Welcome to the wonderful world of AuDHD (Autistic + ADHD) time perception. Here, time isn’t a steady ticking clock – it’s a wibbly-wobbly thing tied to brain chemistry, neural circuits, and your mental state. In other words, if you struggle with “time blindness” (losing track of time, underestimating/overestimating durations, etc.), it’s not because you’re lazy or careless – it’s because your brain literally experiences time differently.

In this post, we’ll dive into the neuroscience-backed reasons behind these time challenges, using relatable examples and metaphors (and a dash of humor). Then we’ll explore practical strategies and tools – ones that work with your unique brain instead of against it – to help make peace with the clock. By the end, you’ll see that you’re not “bad at time” at all; you’re running a brain with a flexible, state-dependent clock. Let’s get into it!

Why Time Feels Different in an AuDHD Brain (Neuroscience-Backed Challenges)

Neurodivergent brains (like those with ADHD, autism, or both – hi, AuDHD folks) often face specific challenges with perceiving and managing time. These aren’t character flaws; they’re rooted in how our brains are wired. Here are some of the common time-related phenomena, explained in human-speak:

Prospective Timing is Noisy (Your Internal Clock Runs on Dopamine)

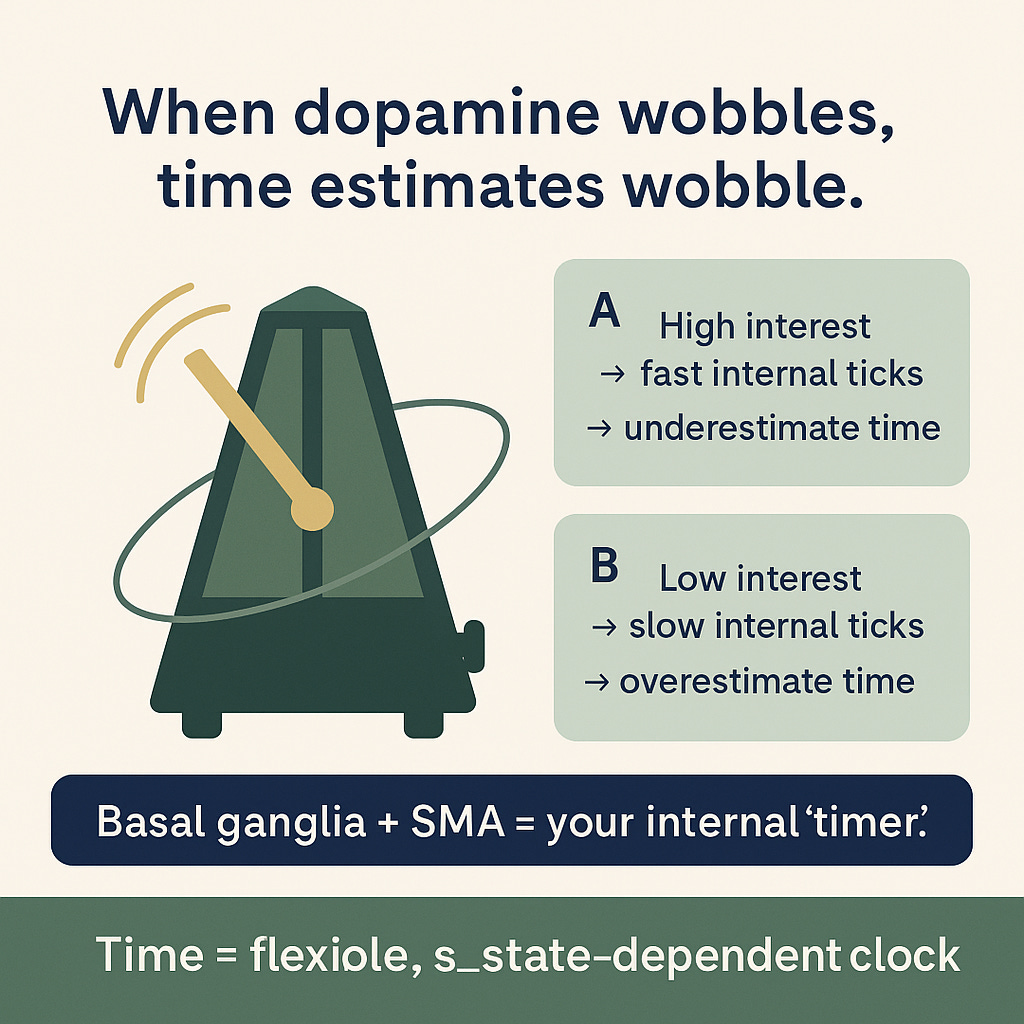

Our brains have an “internal clock” circuit – involving the basal ganglia and supplementary motor area – that keeps track of short time intervals (like seconds or minutes). Think of it like a metronome in your mind. In a neurotypical brain, that metronome ticks at a fairly steady pace. In ADHD, however, the dopamine signals that fuel this metronome can be irregular, making the beats a bit chaotic.

High interest or high stimulation might send dopamine surging and make your internal clock tick faster; boredom or low dopamine might slow that clock down. The result? Estimating durations becomes like trying to guess the tempo of a song when the DJ keeps changing the beat. You might genuinely believe your shower was 5 minutes (internal clock sped up), when it was actually 15. Or you set out to work “for 20 minutes” and find that 45 minutes passed (clock slowed down because you were hyperfocused and lost track).

Neuroscientists have found that the basal ganglia (rich in dopamine-receptive cells) is a key timekeeper, and ADHD is associated with differences in dopamine levels and signaling.

In fact, when people with ADHD take stimulant medication (which increases dopamine), their sense of time often improves.

So if your timing is a bit “noisy,” it’s not a moral failing – it’s brain chemistry. Your internal clock literally ticks differently based on interest and arousal.

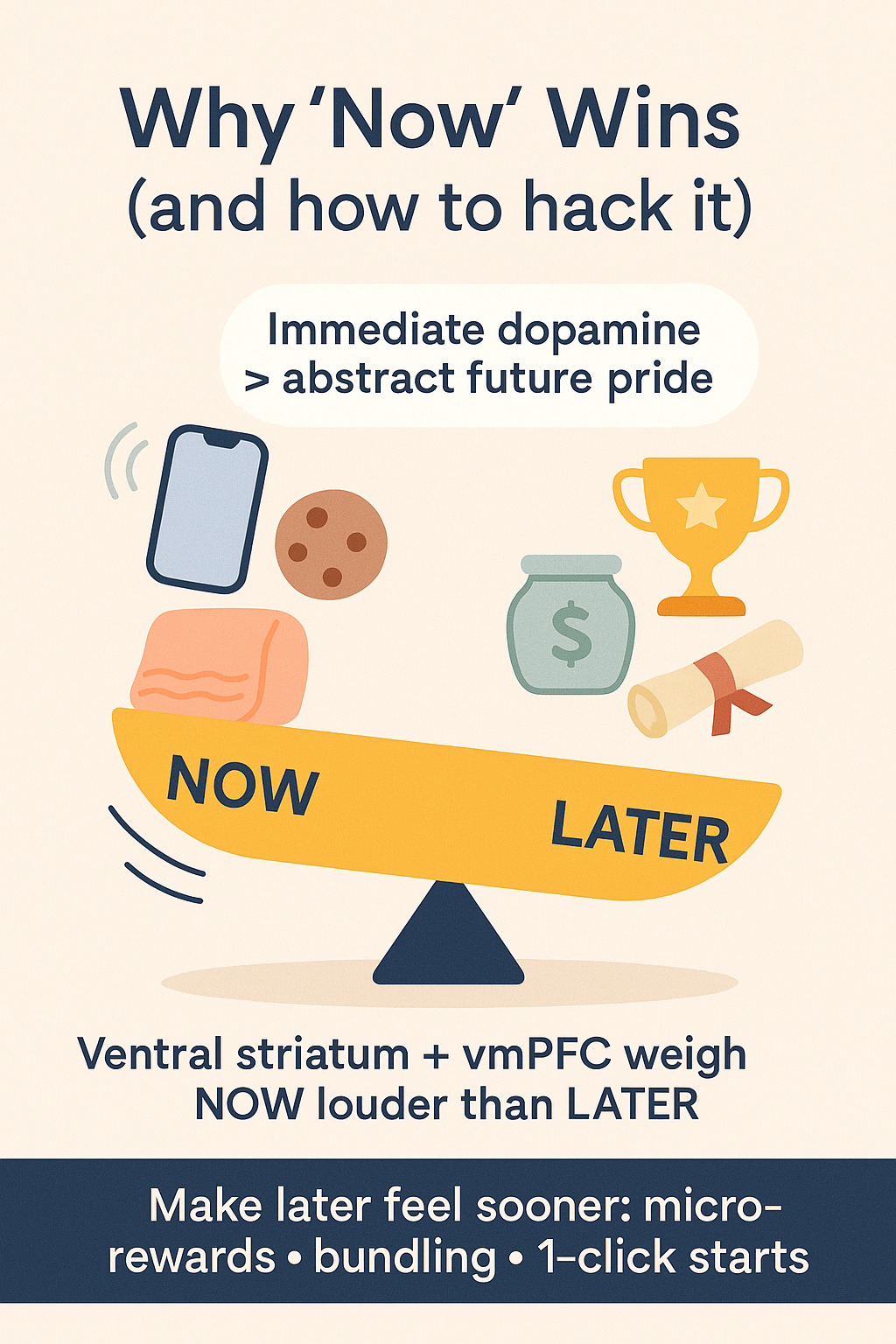

“Now” vs. “Later” – Unevenly Weighted Rewards

AuDHD and ADHD brains don’t weight now vs. later the same way neurotypical ones do. In fancy terms, we have steeper temporal discounting – meaning a reward in the future loses its shine much faster in our minds than an immediate reward. In practical terms: “Future me will be proud if I finish this report by Friday” just doesn’t fire up the brain’s reward center as much as “Scrolling my phone feels good right now.” This isn’t because we lack morals or willpower – it’s dopaminergic valuation math happening in brain regions like the ventral striatum and vmPFC (ventromedial prefrontal cortex). Those areas prioritize immediate, tangible rewards over abstract future ones. The brain basically says, “Hmm, a cookie now vs. a beach body in 3 months? COOKIE NOW!” 🏆🍪.

For example, an AuDHD adult might truly intend to start studying early for an exam (to enjoy the future payoff of a good grade). But each evening, the immediate reward of a favorite video game or the immediate relief of avoiding studying wins out. It’s a constant battle between the “Now” brain (reward circuit demanding something fun or relieving this minute) and the “Later” brain (the logical planner thinking about future goals). Neuroscience backs this up: ADHD studies show reduced activation in the future-planning/value areas when considering delayed rewards.

The “later” reward signals just aren’t as loud.

The takeaway: your brain isn’t choosing to be irresponsible – it’s calibrated to seek dopamine now. Understanding this can help us forgive ourselves and find workarounds (more on that in the strategy section).

An Internal Clock with Variable Speed (Boredom Stretches Time, Hyperfocus Shrinks It)

Ever notice how time crawls when you’re bored, but vanishes when you’re engrossed in something? This effect is dialed up to 11 in AuDHD brains. Our perception of the passage of time is highly state-dependent. When under-stimulated or doing something tedious, you might feel every second trudging by (two minutes of an uninteresting task feels like ten). That’s because low dopamine/norepinephrine in that state makes each tick of your internal clock expand – your brain’s metronome slows, so time feels slow. On the flip side, when you’re hyperfocused on a special interest or an exciting task, you enter a tunnel where hours can disappear in what feels like moments. The neuromodulators (dopamine, etc.) and the brain’s salience network are amped up, effectively speeding your internal ticker and blurring out the clock entirely.

A classic ADHD saying is “there are two times: now and not now.” In hyperfocus, everything outside the “now” drops away – including the sense of time passing. In boredom, “not now” (the time until something rewarding happens) feels interminable. Science has observed this: people with ADHD often underestimate time during engaging activities and overestimate duration during dull tasks.

It’s like living with a rubber band clock that stretches or contracts depending on what state your brain is in.

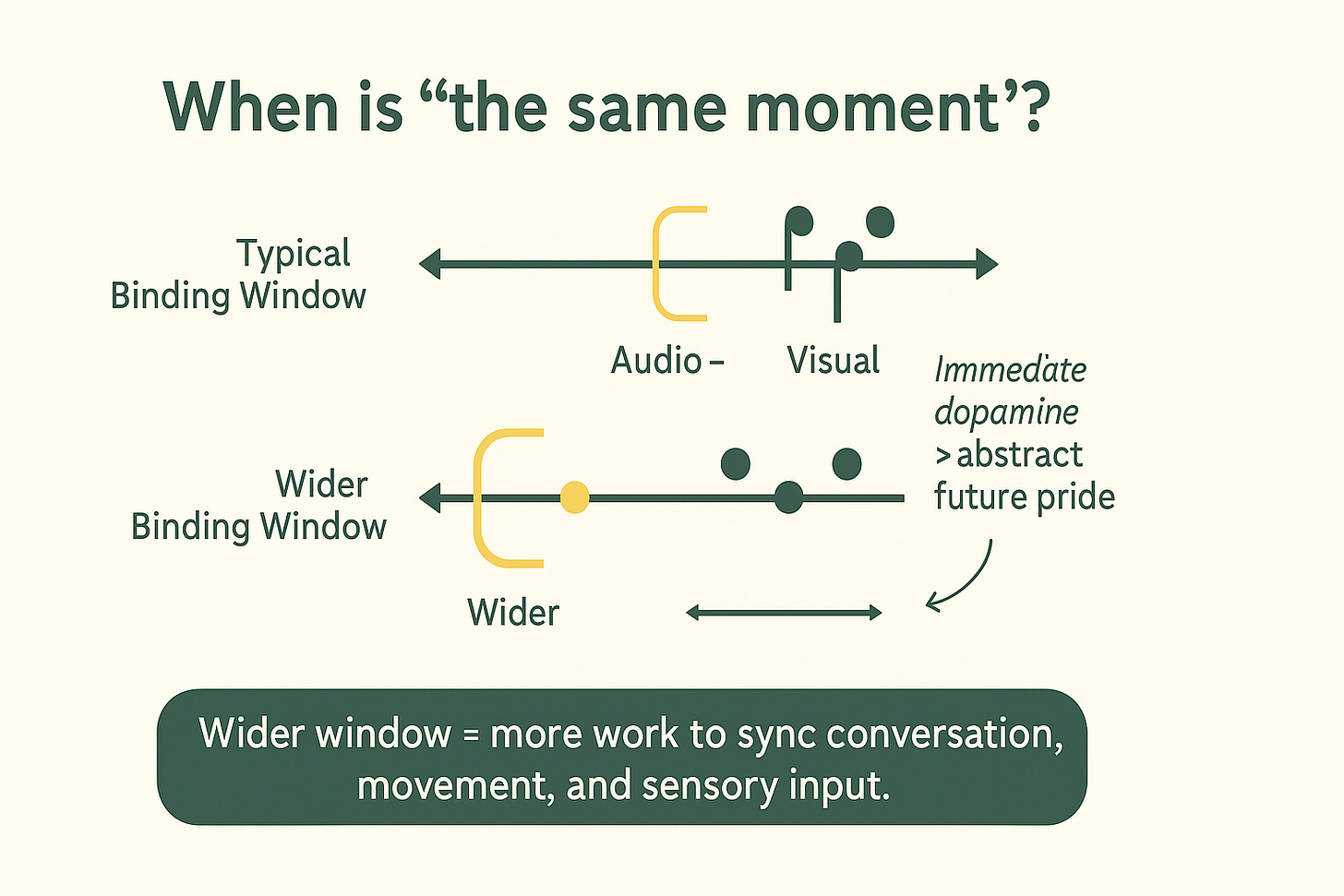

A Wider “Temporal Binding Window” (Especially in Autism)

This one sounds technical, but it’s fascinating: the temporal binding window is the brain’s answer to “how close in time do two things need to happen for me to consider them simultaneous or related?” For most people, sights and sounds that occur within a fraction of a second get merged into one event (“the person’s lips moved and I heard the word – that’s one moment”). Many autistic brains have a wider binding window – meaning the tolerance for linking events is broader.

In real life, this might mean you’re less precise in syncing up multi-sensory information. For example, if someone’s speech audio lags slightly behind their lip movements, a neurotypical person might notice the mismatch quickly, whereas an autistic person might not detect it as readily because their brain still binds it as one event.

How does this affect time perception and social timing? It can make the world feel a half-beat off. Conversations, for instance, have a rhythm – if your internal sense of when it’s your turn to talk is a bit offset, you might accidentally interrupt or pause too long. Or coordinating movements (like in a team sport or dancing) might be harder because your brain’s clock for syncing with others isn’t as tight. It’s like trying to dance to music with a slight delay in your headphones – you can do it, but it takes extra concentration. This broader temporal binding means the brain requires a bit more leeway to decide “things happening close together are part of the same moment.” The downside: processing social and sensory info can cost extra energy and sometimes lead to feeling out-of-sync or overwhelmed. If you’ve ever felt like others are on a slightly different timing wavelength – this could be why.

Temporal Sequencing and Order Memory – The Steps Get Fuzzy

Another challenge: remembering the order and sequence of tasks or events. This is where working memory (a prefrontal cortex job) and the cerebellum (involved in timing and predicting sequences) come into play. Many AuDHD folks can know what steps to do, but holding the order of those steps in mind is like juggling 6 balls in the air – drop one, and the sequence falls apart. For example, say you need to get out the door: you need to shower, then get dressed, then grab the lunch, then find keys, etc. You know all those tasks. But keeping them in an ordered timeline in your head (“first I do X, then Y, then Z”) is surprisingly taxing. Often, by the time you’re on step Y, step Z might slip out of mind, or you do things in an inefficient order.

Neurologically, this relates to executive function weaknesses common in ADHD and also sometimes in autism: the frontal brain networks have to coordinate with memory centers to string events in the right sequence. If those circuits are frayed or underpowered, you get sequencing fray – the mental timeline doesn’t hold tight. It’s why multi-step tasks or following procedures can be exhausting. You might find yourself re-tracing steps or double-checking what comes next constantly. It’s not that you’re incapable of planning – it just takes much more effort to keep the temporal order online in working memory. (Imagine trying to recite the alphabet backwards; it takes work because our brains didn’t automatize that sequence.)

Time-Based Prospective Memory Often Fails (Without External Cues)

Prospective memory = remembering to do something in the future. There are two types:

Time-based: “At 3:00 PM, send the email.”

Event-based: “When I see Sarah, give her the message.”

ADHD/AuDHD brains notoriously struggle with the time-based kind. It’s like scheduling an alarm in your head – except the “alarm clock” in the brain often fails to ring at the right time (unless something external cues it). Research shows that individuals with ADHD are impaired at time-based prospective memory, while their event-based memory is relatively better.

In plain terms, if you rely on “I’ll remember to do X at 3 PM,” chances are 3 PM will come and go, and that task will poof out of mind until something else reminds you (like suddenly seeing the clock at 5 PM and going “oh no!”).

Why is this? One theory: the internal sense of time passing (needed to know “now it’s 3:00”) is unreliable, and the brain’s alerting system is easily outcompeted by whatever is currently grabbing attention. Unless the 3:00 task itself is highly salient or dopaminergically interesting, it won’t win the competition against, say, a captivating YouTube video or an absorbing project. However, event-based intentions (“after my 10:00 meeting, I’ll call the doctor”) piggyback on an external cue – the end of the meeting acts as a trigger. Since ADHD brains are very cue-driven, this is more dependable. Without external cues, a time-based intention is like a sticky note that won’t stay stuck – it drifts away.

If you find yourself missing appointments or deadlines unless you set multiple alarms, this is why. The intention is there, but the brain’s timing circuit doesn’t surface it at the right moment on its own. It needs help (and that’s okay!).

Transition Latency and “Stopping” Inertia

Ever experience the “just one more minute” syndrome when hyperfocused? Or the feeling of your brain refusing to launch into a task you actually need (aka task initiation paralysis)? These are two sides of the same coin: difficulty with transitions – starting, stopping, and switching tasks. In AuDHD brains, transitions are temporal control problems. The brain’s executive control network (fronto-parietal regions) has to shift gears, turning off one task set and booting up another. This is effortful for any brain, but especially if yours is wired for intense focus or needs high interest to get going.

Stopping inertia (hyperfocus lock): When deeply engaged in something (maybe an autistic special interest or an ADHD hyperfocus mode), pulling out of it is painful. It feels like slamming the brakes on a speeding train. There’s neurological friction in disengaging attention and remembering “oh, I need to switch to the next thing.” So you keep saying “one more minute… just need to finish this part…”, and next thing you know, you’ve blown past the intended stop time. The concept of time during hyperfocus practically evaporates, so it requires a huge mental force to break the spell. Without deliberate strategies, transitions can come with a lot of anxiety or discomfort, so the path of least resistance is to avoid switching as long as possible (keep doing what’s rewarding now).

Launch latency (start delay): On the flip side, when you’re not in motion, getting started on a new or unappealing task can feel like trying to ignite damp wood. The “ignition sequence” in the brain sputters. This is often because the next task isn’t providing an immediate reward or clear signal to the brain’s motivation centers. So the engine stalls. You know you need to start that report, but your brain is in neutral, scrolling socials or doing anything else. Neurologically, this may be tied to lower dopamine (nothing exciting to kickstart you) and difficulty the executive network has in configuring a new task set when the payoff is distant or abstract. It’s like your brain is saying, “Why go through the effort of switching? There’s nothing obviously satisfying about that new task… let’s stay here a bit longer.”

Both of these – the difficulty stopping and the difficulty starting – can wreak havoc on schedules and intended timelines. They make transitions sluggish and costly. But as you’ll see next, there are ways to design your day and environment to ease these transitions.

Whew, that’s a lot of brain science! If you’re nodding along thinking “Yes! That’s me!” – the good news is there are compensatory strategies that can help mitigate these challenges. The trick is to work with your brain’s tendencies (externalize what you can, motivate with what actually feels rewarding, etc.) rather than brute-forcing “try harder to be on time” (if it were that simple, we’d have done it!). Let’s move on to the fun part: practical tools and techniques tailored for the AuDHD mind.

Four Practical Strategies (That Respect the Brain You Have)

Managing time with an AuDHD brain means building scaffolds and using creative hacks so you don’t have to rely on an unreliable internal clock or willpower alone. Think of these strategies as turning on GPS because your internal compass is a bit wonky – totally fine and very helpful. Here are four big approaches, each with concrete tips (and a few app/tool suggestions) to reduce time friction:

1. Externalize Time – Let Your Brain Do Brains, Not Clocks

Make time visible and tangible. Since your internal sense of time is variable, offload that job to physical tools. This frees your brain to focus on the task at hand without also trying to be a time-keeper.

Use visual timers and clocks: Big analog clocks (yes, the old-fashioned kind with hands) or visual countdown timers are game-changers. For example, many ADHD folks love the Time Timer – a clock that shows a red disk shrinking as time passes. With a quick glance, you get a visual sense of how much time is left.

There are also apps and desktop widgets that display a countdown or progress bar for a given interval. Pin one where your eyes naturally land (top of your screen, or your desk). It’s like giving your brain a pair of external “eyes” on time. Suddenly, 15 minutes is not an abstract concept – you can see it ticking down.

Auditory cues and alarms: If you tend to hyperfocus and lose hours, set gentle alarms or chimes at intervals (“pomodoro” style, e.g. every 20-30 minutes) or at transition points. A subtle sound can poke your brain, “Hey, 30 minutes passed!” which is often enough to break the spell just enough to decide if you need to switch tasks. Bonus: use distinct tones for different meanings (a soft ding each hour for awareness, a loud alarm when you must stop).

Timeboxing > open-ended to-do lists: Instead of saying “I’ll work on X until it’s done” (which could be infinite), give yourself a time container. For instance, plan 12:30–12:50 email triage, 12:50–1:00 break. Scheduling tasks into blocks forces you to allocate real time to them, which combats the tendency to drastically underestimate how long things take. It also creates natural deadlines to start and stop. Use a calendar or scheduling app to block times, or a simple paper agenda. The key is treating time as a finite slot for each task. Even if you don’t stick 100% to the plan, the act of timeboxing trains your brain to see time as concrete chunks.

State-matching your timer lengths: Not all time intervals work equally well in all brain-states. If you’re under-stimulated (task is boring, brain is sluggish), asking your brain to focus for a full 30 minutes can feel impossible. Try short sprints instead: set a timer for 8-10 minutes and tell yourself you only have to work until it rings – then you can re-evaluate. Often, the hardest part is starting, and once you do 10 minutes, you might continue. Conversely, if you’re engaged or in flow, a 10-minute timer may break your concentration too often – maybe go for a 25-minute or 40-minute block. Adjust the “pomodoro” length based on your current attention level. This respects the fact that AuDHD arousal levels fluctuate. Some days you’re a hare (short bursts), some days a tortoise (steady longer runs).

Big picture visual aids: Consider a whiteboard or wall calendar in your workspace that outlines your day’s timeline or key tasks with time estimates. This external roadmap helps keep you oriented. For instance, a whiteboard might say: “Morning (9-11): Finish design draft (~1.5 hrs). 11-11:15: snack break. 11:15-12:30: Emails (~1 hr).” Seeing it out there reduces the load on your working memory and makes the abstract schedule concrete.

Tools & Apps: Aside from the physical Time Timer, apps like Forest (which grows a tree in a set time to keep you off your phone), or Focus To-Do (Pomodoro timer with task list), or even a simple countdown widget on your phone’s home screen can be great. Use calendar apps (Google Cal, Outlook) to schedule tasks, and set them to notify you. Some people like Notion or Trello to create time-blocked to-do boards. The specific tool matters less than the principle: get time info out of your head and into the world.

Journal Prompt: How do you currently visualize or track time (if at all)? Think of a recent day where time “got away” from you – what external cue might have helped (a timer, an alarm, a written plan)? Jot down one or two concrete changes you could make to externalize time in your daily routine.

2. Make “Later” Feel Sooner – Build Dopamine Scaffolds for Future Tasks

We know the AuDHD brain is all about now. Distant rewards don’t spark action. So, trick your brain by bringing some of that dopamine-driven excitement or reward into the present task, especially for things that are important-but-not-stimulating. I call this “dopamine scaffolding” – creating little supports of enjoyment or immediate payoff to bridge the gap to a future goal.

Immediate micro-rewards: Break a task into bite-sized pieces and give yourself a tiny reward after each piece. Maybe after 15 minutes of writing, you get to watch a funny YouTube clip for 1 minute, or put a sticker in your planner, or literally stand up and do a small happy dance. It sounds silly, but those micro-rewards send a hit of dopamine that tells your brain “nice job, do that again!” Use whatever personally feels rewarding: a bite of chocolate, check a favorite app for 2 minutes, a quick walk outside, play a 30-second snippet of a favorite song – anything that your brain perks up to. By chaining many short “wins,” you keep the dopamine flowing throughout a longer task. Over time, this trains your brain that even normally boring activities have frequent feel-good points along the way, not just at the very end.

Temptation bundling: Pair the dull with the delightful. This means taking something you need to do but find uninteresting, and bundling it with something you love to do. Classic example: Only let yourself listen to that gripping true-crime podcast while doing housework. Or reserve a favorite fancy coffee for when you’re sorting your inbox. The treat provides an immediate positive experience alongside the task. One creative twist: make a playlist that you only play when working on a specific project – your brain will start associating that music with the task and look forward to it. Some people use cozy environments as a reward pairing (e.g. do your budgeting in a comfy chair with a warm blanket and scented candle – engage those senses!). The idea is to coat the task in dopamine syrup so it’s more palatable.

Reduce friction to start (a “friction flip”): Often we don’t start something because there are too many steps before the real work begins (e.g. “Ugh, I have to open the laptop, find the file, etc.”). Flip this by making the very first action stupidly easy and front-and-center. For instance, if you need to write a report, put a direct shortcut to the document on your phone home screen or computer desktop – one tap and you’re in. If you plan to work out in the morning, sleep in your gym clothes or place them by your bed so you literally stumble into them. By hacking your environment to remove the tiniest bits of friction, you can often glide into the task before your brain’s “not now” voice catches up. Another example: keep tools open and ready – if you intend to journal each night, leave the journal open on your desk with a pen on top (one less barrier than having to fetch it from a drawer). Design your environment for one-click go.

Gamify progress: Consider turning tasks into a game for an immediate sense of accomplishment. Apps like Habitica let you earn points (and feed a cute avatar) for completing tasks – giving you that little hit of achievement. Or you can make a progress bar for yourself on paper or a whiteboard, filling in sections as you work (like those charity thermometer charts). Watching the bar fill gives a visual “Yay!” to your brain. Some people respond well to ticking checkboxes off a list – if that’s you, break tasks so you get to check items off frequently. Each check is a mini dopamine hit. Whatever you do, make progress visible and rewarding now, not just at the very end.

Tools & Apps: For temptation bundling, you don’t need a specific app – it’s about creativity (Spotify/YouTube for special playlists, great coffee beans for work time, etc.). For reducing friction, look into features like smartphone widgets or shortcuts (you can often create one-tap shortcuts to a document, app or routine). Apps like IFTTT or Shortcuts (iOS) can automate things (e.g. at 9am, automatically launch my to-do app and play a pump-up song). Gamification tools include Habitica (RPG-style habit tracker) and Forest (mentioned earlier, where you grow a tree by not using your phone while working). Even a simple timer app with built-in break notifications can serve as a reward scheduler. Figure out what kind of instant gratification motivates you, and sprinkle that into your workflow liberally.

Journal Prompt: Think of a task you’ve been putting off because it feels unrewarding. Write down two ways you could make it more immediately enjoyable – what treat, music, or game could you bundle with it? Also, identify one point of friction that makes you avoid the task (e.g. “I hate digging for the files I need”). Brainstorm a change to remove that friction (e.g. “leave the needed file open on my computer”).

3. Reduce the Brain’s Temporal Load with Smart Triggers and Routines

Since remembering timing and sequencing are not our brain’s forte, offload and simplify those functions with external triggers and structured routines. This strategy is about creating an external scaffolding of cues so you don’t have to hold time in your head or use brute-force memory.

If-Then Start Routines: Use implementation intentions, which is a fancy term for pre-deciding a specific cue to start a task. “If X happens, then I will do Y.” Make the cue something that does happen naturally in your day. For example: “If I finish my morning coffee, then I spend 5 minutes planning my day,” or “If I sit down at my desk, then I immediately open the project doc and start a 2-minute warm-up (like typing nonsense or outlining ideas).” The beauty of this is the cue triggers the action, not a clock time. It aligns with how ND brains often work best: in response to events. Often, the hardest part is starting, so having a ritualized start that’s tied to something you already do can bypass the need for motivation. Over time, the action becomes a habit linked to the cue (like Pavlov’s dogs, but you’re training Pavlov’s AuDHD brain 😃).

Event-based reminders > pure time-based reminders: Whenever possible, set up reminders that piggyback on events or locations rather than just schedule alone. Many phones allow location-based reminders (e.g. “When I get home, remind me to feed the cat” or “When leaving work, remind me to stop by store”). You can also use calendar events as triggers: for instance, instead of a lone reminder at 3:00 “Send report,” schedule a calendar event called “Send report” right after your 2:00-3:00 meeting. That way, when the meeting ends, you see “Send report” pop up. Or use the meeting end as your mental cue: “When this Zoom call ends, then I will immediately send that report.” Anchoring tasks to existing daily landmarks (meals, transit, other tasks) leverages the fact that your brain will notice those big events, and can use them as springboards for the next action. Some people even say things like “After I brush my teeth at night, then I’ll set out tomorrow’s clothes” – linking a new task to a well-ingrained routine. This reduces the need to remember when to do something; life events become your reminders.

Pre-decide sequences with checklists (and time estimates): If certain multi-step processes often trip you up (forgetting steps, or not knowing how long each will take), take time when you’re not in the heat of the moment to write a simple checklist for them. For example, a morning routine checklist: list out “1) 5 min – take meds, 2) 10 min – shower, 3) 5 min – get dressed, 4) 5 min – gather bag, 5) 2 min – keys & lock door”. Write the estimated minutes next to each. This does a few things: (a) You don’t have to mentally juggle the steps – you can follow the list. (b) The time estimates help combat that distortion where you think showering takes 2 minutes but it’s really 10. (c) It creates a game/goal (“Let’s see if I can do ‘kitchen cleanup – 8 min’ as listed!”). You can do this for any recurring routine – after-work shutdown, project setup, even a checklist for “leaving the house” (ever get to the car then realize you forgot something? A list by the door fixes that). Bonus: lamination – some folks laminate their routine checklists so they can reuse with a dry-erase marker daily. The idea is to transfer the burden of sequencing from your brain to a piece of paper. And by including time estimates, you also train your sense of how long things actually take, improving future planning.

Automate and batch whenever possible: Use technology to take care of timing for you. For example, set bills to auto-pay (so you don’t need to remember due dates), use apps to schedule routine emails or posts, or batch similar tasks together so that one session covers many future needs (like meal prepping on Sunday so each weekday you’re not dealing with cooking timing). Every task you can routinize or automate is one less timing challenge on your plate. If you always forget to take medication at 3 PM, use a smart pill dispenser or an app alarm that won’t shut up until you confirm. Smart assistants (Alexa, Google Home, Siri) can be programmed with routines too: e.g., “Hey Siri, when it’s 9pm, remind me to check that I locked the doors.”

Tools & Apps: Leverage reminder apps – Todoist, Google Keep, Apple Reminders – most allow tagging a reminder to a location or to a specific time and day. Calendar programs can auto-schedule recurring events (use them for things like “Monthly report due – prepare one week ahead” with alerts). For checklists, any notes app works; there are also specialty apps like TickTick or Microsoft To Do that let you create template checklists. Some folks use Notion databases for routines. Also explore automation tools: IFTTT (If-This-Then-That) can connect apps and events (like “text me if it’s going to rain tomorrow so I remember to bring umbrella”), or phone automation (“at 10pm, play a sound and announce ‘begin wind-down’”). The more your environment nudges you, the less pressure on your brain to keep track of it all.

Journal Prompt: Identify one thing you repeatedly forget or struggle to start on time. What’s a natural event you could tie that task to? (e.g. “After dinner, I will do X” or “When I arrive at the office, I do Y”). Write an “If-Then” statement for it. Also, think of a complex task or routine that stresses you – list out the steps and how long each takes. How does seeing the steps written out make you feel about the task?

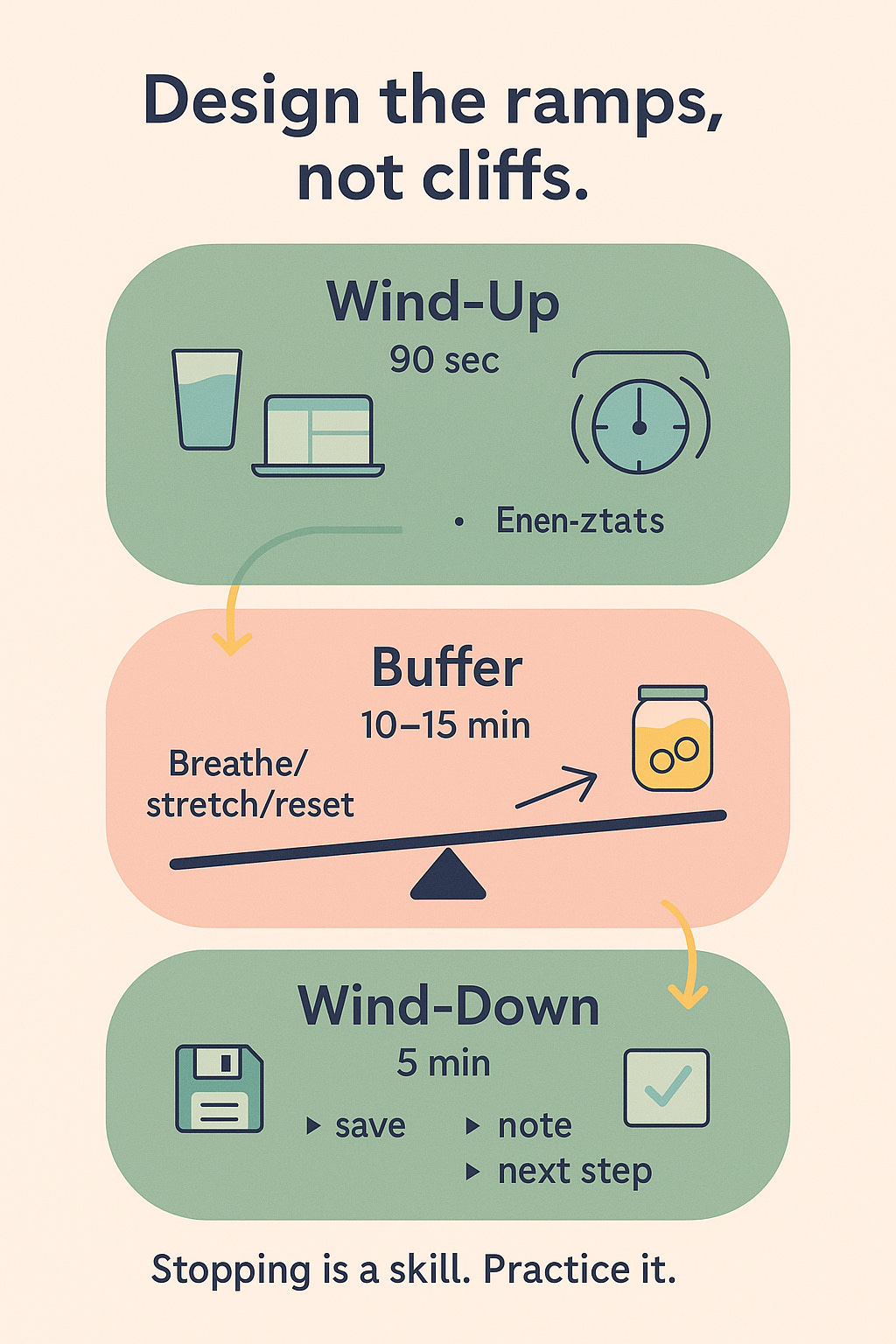

4. Design Compassionate Transitions – Wind-ups, Buffers, and Wind-downs

Because switching states is hard, build gentle ramps and brakes for your brain around activities. Instead of expecting instant on/off like a light switch, treat your transitions like a old-fashioned car that needs a warm-up in the morning and some coasting time before a stop. This reduces the jarring effect of switching tasks and helps avoid those “stuck in hyperfocus” or “stuck in procrastination” moments.

Wind-up rituals: Create a short ready-to-start routine that signals your brain it’s time to shift into work mode (or whatever mode you need). It could be 90 seconds long: for example, you might pour a glass of water, do a quick stretch, open only the tabs or apps you need for the task, and start a timer for the first work interval. This predictable sequence acts like the ignition sequence of a rocket – it tells your brain “we’re preparing for launch.” Over time, your brain learns that this ritual = we’re getting started, which can decrease the mental resistance to beginning a task. Some people put on specific “focus clothes” or a certain hat to symbolize “focus time starting” – hey, whatever works! The point is to have a consistent set of actions that you initiate before diving into a task, especially one you tend to avoid. It eases you in gently rather than a cold start.

Buffers between blocks: Whenever you can, schedule buffer zones on your calendar between tasks or meetings. Even just 10-15 minutes of white space can work wonders. Use that time to consciously switch gears: stand up, move around, get a snack, or just do nothing and let your brain catch up. Imagine you’ve been deep in analysis for 2 hours and your next block is a creative meeting – if you try to go directly, your brain might still be in analysis mode for the first part of the meeting. But if you give yourself a 15-minute “palette cleanser” break, you’ll be much more present in the next thing. Buffers also protect you from the domino effect of one thing running late and then everything else derailing. Think of them as shock absorbers in your schedule. It’s an act of self-compassion to acknowledge you need a breather to transition (most people do, neurodivergent or not!). So, if you have control over your schedule, don’t cram back-to-back if you can help it – pad it. If someone schedules things for you, advocate for short breaks when possible.

Wind-down alarms and closing routines: One big hyperfocus trap is not knowing when to stop – so set an alarm a few minutes before you actually need to stop a task. When the alarm goes, initiate a closing routine for that activity. Example: you’re hyperfocused on writing code, but you need to leave at 5pm. Set an alarm at 4:50. When it rings, take 5 minutes to wrap up: write a quick note on where to resume next time, hit save, close your tabs or applications, and maybe note a “next step” for tomorrow. This ritual of closing out not only helps your brain release the task (“we’re done for now, it’s safe to stop”), but also makes it easier to restart later because you left yourself breadcrumbs. A wind-down might also include a small reward or relaxing action as you shift (like making a cup of herbal tea after shutting the laptop). The key is to have a consistent sign-off procedure so that “stop” feels natural and satisfying rather than abrupt. Over time, your brain will get used to the idea that stopping is part of the process, not an unpleasant wrenching away.

Protect your sleep transition: One of the most important transitions is day-to-night. Many AuDHD folks get a “second wind” at night or lose track of time and end up with poor sleep. Design a bedtime wind-down that works for you: set an alarm for when to start getting ready for bed, then follow a routine (lights dimmed, devices off or on night mode, perhaps reading or listening to calming music). Treat it like landing a plane: start descent well before the scheduled landing. If you just try to crash into bed from 100 mph daytime mode, your brain might refuse to shut off. Gentle routines can cue the body and mind that it’s okay to let go for the day.

Tools & Apps: Use the alarm features liberally – many calendar apps let you add a “15 min before” alert for meetings (that can be your cue to wrap up what you’re doing). There are apps like Stretchly or Timeout for computers that remind you to take breaks (good for inserting buffers). Smartphone bedtime modes can auto-dim and even send you a reminder that “It’s time to start winding down for bed.” You might also look into meditation apps or YouTube videos with short guided routines for starting or ending work. Even a simple checklist (“End-of-day shutdown: 1) Save work, 2) write 3 tasks for tomorrow, 3) pack bag, 4) turn off desk lamp”) stuck to your wall can help ensure you have a closure practice. The trick is consistency: use the same routine regularly so it becomes second-nature.

Journal Prompt: Reflect on a recent time you had to abruptly switch from one task to another – how did it feel? What could an ideal buffer or transition have looked like for that switch? Write down a simple “start ritual” you’d like to try before a challenging task, and a “stop ritual” for when you finish. How do you hope these will make you feel during transitions?

Quick “Try-Today” Time Hacks – Tiny Experiments

That was a lot of strategies! It might feel overwhelming to overhaul your whole approach to time. Don’t worry – you can start small. Here are a few bite-sized experiments to try, even as soon as today. Pick one or two that resonate and see how they feel:

Put a big countdown timer for your next activity in plain sight. For example, if you have something at 4pm, set a countdown on your computer desktop or phone that says “Time until 4:00 meeting” and let it tick. This visual urgency can keep “later” from completely disappearing from your now. It’s like bringing the future into the present moment.

Timebox one task for 12 minutes – then stop on purpose. Choose a task (ideally one you’ve been avoiding or one you tend to get lost in). Set a 12-minute timer. Work on it with focus until the timer rings even if you’re not finished. Then practice stopping. This teaches your brain that it’s okay to pause; you’ll come back to it. Stopping intentionally is a skill, and this exercise builds it. You might be surprised – sometimes a brief sprint is enough to break the ice or make a dent, and you can always do another 12 minutes later.

Convert one “3:00 PM reminder” into an event-based trigger. Identify a reminder or task you’ve set for a specific time that you keep missing. Change it to an event-based cue. For example, instead of “Take medication at 3:00,” try “After lunch (or when I get up for a snack in afternoon), take medication.” Or set a phone reminder not at 3:00 exactly, but “when I leave the office.” You can often do this in reminder apps by selecting a location or by simply mentally planning it (“I tape the note ‘send the report’ on my monitor, so when my meeting ends and I see it, I’ll remember”). See if tying it to an existing habit/routine helps you execute it better.

Add duration labels to 3-5 of your daily routines, then race the clock. Pick a few routines you do often (morning get-ready, post-work tidy, checking email, kitchen clean-up, etc.). Estimate and write down how many minutes each takes (“Email catch-up – 15 min”, “Kitchen reset – 8 min”, “Shower + dress – 10 min”). Now make a game of trying to meet or beat those times using a timer. For instance, start a stopwatch when you begin cleaning the kitchen and see if you can finish around 8 minutes. This gamification serves two purposes: it makes boring chores a bit more engaging (you’re challenging yourself), and it helps calibrate your internal clock by comparing your estimate vs. actual. If you guessed poorly, adjust the label next time without judgment – you’re learning! Over time you get better at judging time, and the tasks feel more like mini-competitions than drudgery.

Body double or co-work for a set time. If you struggle to start or stick to a time block, try the body double technique for just one work session. This could be asking a friend to sit with you (even virtually on a video call) while you both do separate work for 30 minutes. Or join a virtual co-working room (services like Focusmate pair you with a stranger for accountability at a scheduled time). Knowing someone is there in real time often provides just enough external structure to keep you on track. It’s an immediate strategy especially if you have something urgent you’re avoiding – schedule a 25 or 50-minute Focusmate session and let the social pressure work its magic.

Remember, these are experiments, not permanent commitments. Try one and treat it like collecting data on yourself. If it helps – fantastic, add it to your toolkit. If not, no harm done, try a different one. Every brain is unique, so part of this process is discovering what clicks for you.

Final Thoughts: It’s Not You, It’s Your (Awesome) Brain

Living with an AuDHD brain in a neurotypical world can make time feel like an enemy – always late, always slipping away, always causing stress. But the big takeaway here is: you’re not inherently “bad at time.” You experience time differently because your brain wiring — the chemistry, circuits, and state-dependent nature of it — is different.

And that brain, while challenging in some areas, also grants you incredible strengths (creativity, hyperfocus superpowers, unique perspectives).

Think of it this way: you’ve been trying to play a game of clock management on “hard mode” without knowing the rules were skewed. Now you know. It’s neurological, not a personal failing. With that knowledge, you can drop the shame (it’s not laziness or lack of caring) and pick up the tools that level the field for you – timers, routines, external cues, and compassionate pacing.

Becoming more time-effective is not about suddenly forcing your brain to tick to a rigid schedule; it’s about building supports that meet your brain where it is. When you externalize time, add rewards, use smart triggers, and cushion your transitions, you’re essentially giving your brain glasses for its time blindness. The world comes into focus a bit more, and the friction of everyday life drops.

Lastly, embrace a mindset of experimentation and self-compassion. Some tricks will work, some won’t, and that’s okay – try things, keep what helps, toss what doesn’t!

Every small win (like being on time to something, or smoothly switching tasks without an hour of procrastination) is proof that you can thrive with the brain you have. Over time, those wins build confidence, and you might even find pride in how you’ve creatively hacked your time challenges.

You’ve got a brain that sees the world in a unique way – including how it sees time. With a few adjustments and tools, you can turn what feels like a liability into just another aspect of yourself you skillfully manage. The clock doesn’t have to be your nemesis. In fact, with practice, it might just become a supportive friend.

Now, go forth and time-bend with your newfound knowledge – and remember to celebrate each success, no matter how “small” it seems. After all, as an AuDHD brain, you’re navigating time in your own way… and that’s pretty amazing.

Sources:

Schroeder, W. & Allen, S. ADHD and Beating Time Blindness. Just Mind Counseling (2022). – Neuroscience of time perception (basal ganglia, dopamine) and ADHD

Maranto, E. The ADHD Time Warp: Navigating the Maze of Time Blindness. Sage Therapy (2023). – Neurological basis of “time blindness” and practical tips for ADHD time management

Zhou, H. et al. Audiovisual temporal processing in ASD and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Journal 8, 75 (2022). – Research finding that a widened temporal binding window (less sensitivity to timing differences) is a feature in autism

Altgassen, M. et al. Time-based vs. event-based prospective memory in ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology (2012). – Studies showing ADHD adults and kids struggle more with time-based prospective memory than event-based